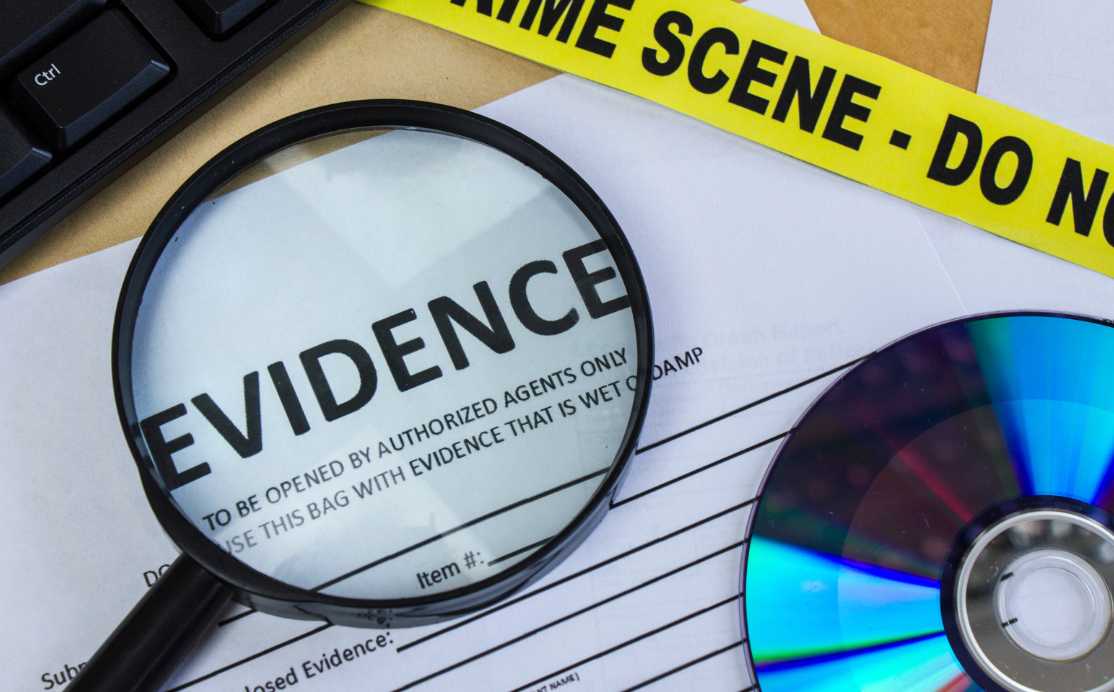

Circumstantial evidence plays an important role in legal proceedings, particularly under the Indian Evidence Act, of 1872.

In India, many criminal cases are adjudicated based on circumstantial evidence, especially when direct evidence such as eyewitness testimony is unavailable.

While circumstantial evidence might not directly prove a fact, it creates a chain of circumstances that strongly point toward a particular conclusion.

What is Circumstantial Evidence?

Circumstantial evidence refers to indirect evidence that requires the judge or jury to make inferences about a fact.

Unlike direct evidence (e.g., eyewitness testimony), circumstantial evidence does not directly prove a fact but relies on a series of facts that, when considered together, lead to a logical conclusion.

It typically involves physical evidence (like fingerprints, DNA, etc.), the accused’s behavior, or other events that point toward the accused’s guilt.

In India, the Indian Evidence Act, of 1872 governs the use and admissibility of both direct and circumstantial evidence.

According to Section 3 of the Act, “evidence” includes both oral testimony and documentary evidence, along with circumstantial evidence that can substantiate the case.

Circumstantial evidence becomes especially crucial in cases where there is no direct evidence available to prove the guilt of the accused.

Conditions to Fulfill

For circumstantial evidence to be admissible and reliable, several conditions must be met, as established through judicial precedents:

#1 Conclusive Chain of Events

The Supreme Court of India has laid down the principle that circumstantial evidence must form a continuous, unbroken chain that leads to only one conclusion: the guilt of the accused.

This was highlighted in the landmark case of Hanumant v. State of Madhya Pradesh (1952).

In this case, the Court laid down that every link in the chain of circumstances must be conclusively established, and the chain should be so strong that it leaves no room for any other hypothesis except the guilt of the accused.

#2 Exclusive Hypothesis of Guilt

The circumstances should exclude any other reasonable hypothesis except the guilt of the accused.

This means that the evidence should point unequivocally towards the accused and leave no possibility of an innocent explanation.

The Court highlighted this principle in Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra (1984), where it was held that the conviction based solely on circumstantial evidence is permissible, provided the evidence is consistent and points solely to the guilt of the accused.

#3 Proximity and Motive

Circumstantial evidence often relies on factors such as the proximity of the accused to the crime scene or the motive behind the crime.

In State of U.P. v. Satish (2010), the Court explained that motive could play a significant role in determining guilt when supported by a complete chain of circumstantial evidence.

#4 No Contradictions

There must be no contradictions in the series of events that form the chain of circumstances. If contradictions exist, the entire case built on circumstantial evidence can collapse.

In Prem Thakur v. State of Punjab (1983), the Court acquitted the accused as the circumstantial evidence did not sufficiently prove guilt.

Importance of Circumstantial Evidence

In Indian criminal jurisprudence, circumstantial evidence has emerged as a cornerstone in securing convictions, particularly when direct evidence is unavailable.

The Indian judiciary has acknowledged that relying solely on direct evidence can sometimes be insufficient due to various limitations such as the non-availability of witnesses or inconsistencies in their testimony.

#1 Reliable in the Absence of Direct Evidence

Many heinous crimes, like murder or rape, occur without any eyewitnesses. In such cases, circumstantial evidence often becomes the only available tool for the prosecution.

For instance, in the case of Laxman Naik v. State of Orissa (1995), the accused was convicted of rape and murder solely based on circumstantial evidence.

#2 Establishing Motive and Intent

Circumstantial evidence often helps establish the motive and intent behind a crime. While direct evidence might provide facts, circumstantial evidence weaves together the motive, behavior, and actions of the accused to point towards guilt.

As seen in the case of State of Gujarat v. Kishorebhai Nathalal Patel (2017), the motive was a critical factor in forming a complete picture of the crime.

#3 Flexibility and Versatility

Unlike direct evidence, which can be subject to errors like witness misidentification or false testimony, circumstantial evidence often relies on physical facts that are less prone to manipulation.

DNA evidence, forensic analysis, and other such elements can provide solid grounds for establishing guilt.

#4 Satisfying Burden of Proof

The burden of proof in criminal cases lies on the prosecution, which must prove the guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Circumstantial evidence, when forming a strong and consistent narrative, can meet this burden effectively.

The case of Sanatan Naskar v. State of West Bengal reiterated that circumstantial evidence must form a complete chain leading to the accused’s guilt without any other plausible explanation.

#5 Corroboration of Other Evidence

Circumstantial evidence often plays a key role in corroborating other types of evidence. In cases where there is partial direct evidence or weak witness testimony, circumstantial evidence strengthens the prosecution’s case.

For instance, forensic evidence like bloodstains or fingerprints can confirm the involvement of the accused even when no direct witness exists.

This can provide the needed confirmation in cases where other evidence is weak or inconsistent.

#6 Avoiding Witness Manipulation

Witnesses can be influenced, coerced, or tampered with, making their testimony unreliable. Circumstantial evidence is immune to such manipulation, as it often involves objective facts like forensic data, surveillance footage, or electronic records.

This reliability makes circumstantial evidence invaluable in ensuring justice when witness testimony may be compromised.

#7 Helps Establish Intent and Motive

Circumstantial evidence is instrumental in establishing the intent and motive behind a crime. Often, direct evidence might only point towards the fact that a crime was committed but may not explain the reasons behind it.

Circumstantial evidence can fill in these gaps by linking the accused’s actions, behavior, and relationship to the victim or crime scene, as seen in cases like State of Gujarat v. Kishore bhai Nathalal Patel (2017)

#8 Assists in Complex Crimes

In complex criminal cases, especially involving organized crime, financial fraud, or white-collar crimes, direct evidence might be scarce or hard to come by.

Circumstantial evidence, such as financial records, phone logs, or digital footprints, becomes critical in piecing together the events leading to the crime.

These can form a detailed chain of actions, helping investigators and the court understand how the crime was executed

#9 Resilience in Absence of Direct Evidence

In many criminal cases, direct evidence may not be available at all—either due to the crime being committed in secrecy or a lack of witnesses.

In such scenarios, circumstantial evidence often provides the only basis for conviction. The Indian judiciary has consistently upheld that a conviction can be based solely on circumstantial evidence, as long as it meets stringent legal requirements, as reiterated in Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra (1984)

Landmark Caselaws Relating to Circumstantial Evidence

Several landmark judgments have shaped the understanding and importance of circumstantial evidence in India:

- Hanumant v. State of Madhya Pradesh (1952): This case is foundational in understanding the doctrine of circumstantial evidence in India. The Court emphasized that the circumstances must be consistent with the guilt of the accused and inconsistent with any hypothesis of innocence.

- Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra (1984): The Court held that circumstantial evidence can be the sole basis for conviction if it meets stringent conditions—fully established circumstances, an exclusive hypothesis of guilt, and no room for any alternative explanation.

- State of U.P. v. Satish (2010): In this case, the Supreme Court examined the delay in filing an FIR and ruled that it would not affect the credibility of circumstantial evidence, provided the evidence is reliable and points conclusively towards guilt.

- Rajendra Pralhadrao Wasnik v. State of Maharashtra (2013): This case dealt with the possibility of false implication. The Court held that circumstantial evidence must rule out the likelihood of false implication and point exclusively towards the accused’s guilt.

- Prem Thakur v. State of Punjab (1983): The Supreme Court ruled that mere proximity between the accused and the victim is insufficient for conviction. In this case, the prosecution’s reliance on circumstantial evidence fell short of conclusively proving guilt.

Verdict

Circumstantial evidence is a vital aspect of the Indian legal system, especially under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Although it is indirect in nature, circumstantial evidence can form the basis of a conviction if it meets the established legal standards.

The chain of events it creates must be complete and conclusive, leaving no reasonable doubt about the accused’s guilt.

Indian courts have repeatedly upheld the importance of circumstantial evidence, recognizing its role in situations where direct evidence is either unavailable or insufficient.

Through landmark cases such as Hanumant v. State of Madhya Pradesh and Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra, the judiciary has laid down stringent principles for evaluating such evidence, ensuring that justice is not compromised.

Thus, while circumstantial evidence may have its limitations, its correct application under the law ensures that it remains a powerful tool in the hands of the Indian judiciary.