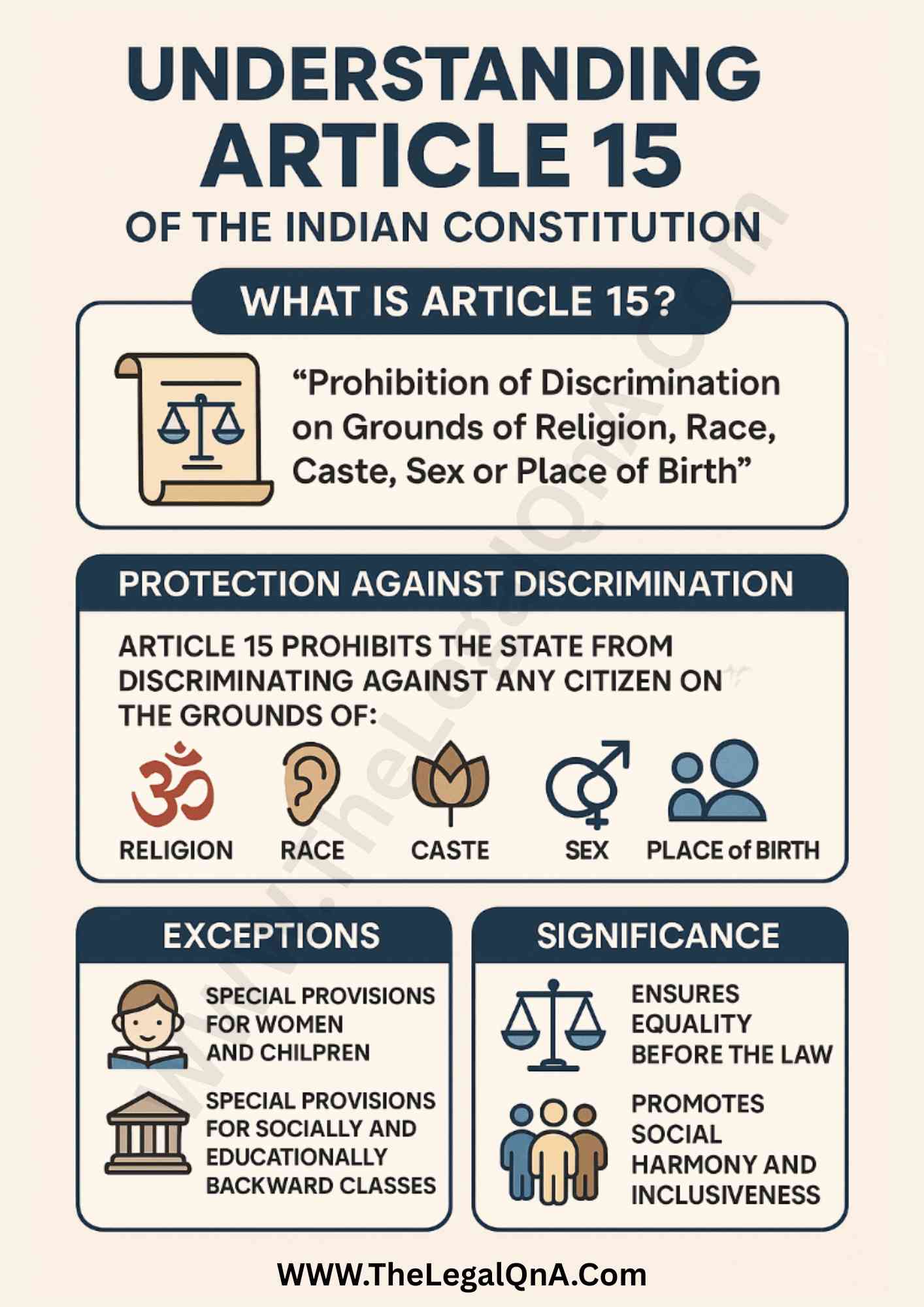

Article 15 of the Constitution of India prohibits discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. It ensures equality by banning prejudicial treatment and permits affirmative action to uplift disadvantaged groups, thereby fostering social justice and integration.

Article 15 of the Constitution of India stands as one of the most significant provisions safeguarding the principle of non-discrimination in the country.

Enshrined as a fundamental right, it prohibits the State from discriminating against any citizen on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth.

Over the decades, this article has been at the heart of transformative judicial decisions, legislative reforms, and vigorous public debates.

India is a land of immense diversity—home to multiple religions, cultures, and languages. While this diversity enriches the nation, it has also been a source of deep-rooted discrimination for centuries.

To safeguard the rights of its citizens and ensure equality, the Indian Constitution grants a set of Fundamental Rights, including protection against discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth.

The Harsh Reality of Discrimination in India

Despite legal safeguards, discrimination has left a lasting imprint on Indian society. Before independence, caste and religious biases dictated social hierarchies, often leading to extreme injustices like untouchability.

Though legally abolished, remnants of these discriminatory practices still surface in various parts of the country.

Even today, newspapers frequently report incidents of caste-based violence—women assaulted for fetching water from community wells, individuals ostracized for entering temples, or lower-caste citizens attacked for challenging social norms.

These stories are not just headlines; they reflect a painful reality that continues to haunt certain sections of Indian society.

To counter such prejudices, Article 15 of the Indian Constitution stands as a beacon of hope. It explicitly prohibits discrimination by the State on five grounds:

- Religion – No citizen can be treated unfairly based on their religious beliefs.

- Race – Racial discrimination, though less common, is strictly forbidden.

- Caste – The caste system, once deeply entrenched, cannot dictate social privileges or restrictions.

- Sex – Gender-based discrimination, including against women and LGBTQ+ individuals, is unconstitutional.

- Place of Birth – A person’s region of birth cannot be a basis for discrimination in opportunities or rights.

Historically, India’s social structure was divided into hierarchical castes, with the so-called lower castes facing systemic oppression.

While legal measures have been introduced to uplift marginalized communities, caste-based biases still manifest in everyday life. Incidents of violence, social exclusion, and economic disparity continue to reflect these age-old divisions.

Gender & LGBTQ+ Discrimination

Discrimination isn’t just about caste or religion—it extends to gender and sexual orientation. Women have long been subjected to unequal treatment, whether in education, employment, or personal freedoms.

Similarly, members of the LGBTQ+ community have historically faced legal and social discrimination.

A landmark moment came in 2018 when the Supreme Court struck down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, finally decriminalizing same-sex relationships and acknowledging the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals.

India’s Linguistic Diversity & Social Biases

India officially recognizes 22 languages under the 8th Schedule of the Constitution, but in reality, over 1,500 languages and dialects are spoken across the country.

Hindi, the most widely spoken language, is used by about 44.63% of the population. However, language has also been a ground for discrimination, often leading to regional and cultural divides.

Scope of ‘Discrimination’ Under Article 15

Discrimination occurs when a person is treated unfairly compared to others in similar circumstances or when they are placed on equal footing despite differences in their situation.

For instance, expecting a pregnant woman or a person with disabilities to meet the same physical standards as others without reasonable accommodation would be discriminatory.

In legal terms, discrimination is unjustifiable unless it is based on rational and objective grounds.

What Does Article 15 Prohibit?

Article 15 of the Indian Constitution explicitly prohibits discrimination by the State on five specific grounds:

- Religion – No person should be denied access to public places, benefits, or policies solely based on their religion. A government scheme or policy favoring or excluding people of a particular faith would be unconstitutional.

- Race – Ethnic origin cannot be a basis for discrimination. For instance, an Indian citizen of Afghan descent should have the same rights as a person of native Indian heritage.

- Caste – The article primarily aims to curb caste-based discrimination, especially atrocities against historically oppressed groups. The law ensures that no one is treated unfairly due to their caste, whether they belong to Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), or Other Backward Classes (OBC).

- Sex – No individual should face bias based on gender identity. This includes discrimination against women, transgender persons, and other gender minorities in areas such as employment, education, or public facilities.

- Place of Birth – The place where someone is born should not determine their rights or opportunities. For example, a person born in Bihar should not be denied job opportunities in Maharashtra simply due to their place of birth.

Does Classification Always Mean Discrimination?

People often assume that any form of differentiation amounts to discrimination, but the Supreme Court has made it clear that not all distinctions violate Article 15.

For a law or policy to be discriminatory, it must create an unjust disadvantage. However, when classification is based on reasonable criteria, it does not fall under the ambit of unconstitutional discrimination.

The Kathi Raning Rawat v. State of Saurashtra (1952) case challenged a law that created special courts for trying offenses like murder and robbery in specific areas. The petitioners argued that this was discriminatory as it treated individuals differently based on their place of residence. The Supreme Court ruled that not all legislative classifications amount to discrimination. Since the law applied based on offenses committed in certain areas rather than personal identity factors, it was considered a valid classification, not discrimination.

In John Vallamattom v. Union of India (2003) A Christian petitioner challenged the Indian Succession Act, 1925, which prevented Christians from making death-bed bequests for religious or charitable purposes. This restriction did not apply to Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, or Parsis. The Supreme Court ruled the provision unconstitutional, as it unfairly restricted Christians alone, without any reasonable justification. Since the law disproportionately targeted a specific religious group, it was struck down as discriminatory.

What About Reservations? Is It Discriminatory?

A common question arises: If treating people differently is discrimination, then isn’t reservation (affirmative action) a violation of Article 15? After all, why should two candidates with the same qualifications be treated differently for a job or an exam?

The answer lies in reasonable classification. Reservation is not about giving undue advantages; it is about leveling the playing field for communities that have historically been denied opportunities due to systemic discrimination.

The law recognizes that treating unequals as equals is itself a form of injustice. By ensuring fair representation for marginalized groups, reservation seeks to achieve substantive equality, not inequality.

Historical Context and the Drafting of Article 15

Prior to India’s independence in 1947, the subcontinent was marked by deep-rooted social hierarchies and discrimination.

The caste system, colonial policies, and traditional social norms ensured that millions of Indians—particularly those from the lower castes, tribes, and marginalized communities—were denied basic rights and opportunities.

Discrimination was rampant not only in employment and education but also in access to public amenities and political participation.

The Indian independence movement, however, was also a movement for social justice. Leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, B.R. Ambedkar, and Jawaharlal Nehru emphasized the need for an egalitarian society.

They believed that the struggle for freedom was intrinsically linked to the struggle for social justice. This sentiment laid the groundwork for the drafting of a constitution that would guarantee equal rights for all citizens.

Debates in the Constituent Assembly

When the Constituent Assembly convened to draft the new constitution, one of the most pressing issues was the eradication of social discrimination.

Debates in the Assembly were intense, with members arguing about the precise grounds on which discrimination should be prohibited.

Some members proposed an extensive list of factors, including family background and descent, while others feared that overly specific provisions might perpetuate divisions.

B.R. Ambedkar, the principal architect of the Constitution, played a pivotal role in shaping the discussion around non-discrimination.

He argued that the language of the article should be broad enough to cover all forms of arbitrary discrimination without being so detailed as to limit future interpretations. As Ambedkar famously stated during the debates,

“We must ensure that our constitution is a living document that can adapt to the challenges of time without being fettered by rigid definitions.”

This insistence on a flexible yet robust prohibition against discrimination led to the formulation of what is now known as Article 15.

The Evolution from Draft Article 9 to Article 15

Initially, the draft version of the article was numbered differently. In the early drafts of the Constitution, the provision prohibiting discrimination was known as Draft Article 9.

Over time, after several amendments and debates, the provision was renumbered and eventually became Article 15.

The final text was the result of a careful balancing act: it needed to provide a strong guarantee against discrimination while also allowing the State the flexibility to implement affirmative action measures.

Ambedkar’s vision was not only to prohibit discrimination but also to empower the State to take special measures for the advancement of historically disadvantaged groups.

This dual mandate is reflected in the later clauses of Article 15, which permit the State to enact positive discrimination policies for women, children, and other marginalized communities.

Text and Structure of Article 15

Article 15 is divided into several clauses, each addressing different aspects of discrimination and affirmative action. In this section, we examine each clause in detail.

Clause 1: Prohibition of Discrimination by the State

As per Article 15(1) of the Indian Constitution,

“The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them.”

This provision guarantees that no citizen shall face unjust treatment solely based on their identity factors. However, despite these constitutional protections, discrimination persists in various forms, as evident from historical and contemporary instances.

The scope of Article 15(1) is extensive, prohibiting discrimination in civil, political, and economic matters. Below is a detailed analysis of its application to different categories:

#1 Religion

The principle of secularism under the Indian Constitution ensures that religion should not be a ground for discrimination by the State. Article 15(1) bars the State from favoring or disfavoring any citizen based on religious identity.

State of Rajasthan v. Pratap Singh (1960)

- The case challenged an order under Section 15 of the Police Act, 1861, which designated certain areas as ‘disturbed areas’ and required the inhabitants to bear the cost of additional police deployment.

- The Supreme Court ruled that exempting Harijans and Muslims from such liability, without any reasonable justification, violated Article 15(1). The order was deemed unconstitutional as it discriminated based on religion.

Danial Latifi v. Union of India (2001)

- This case examined the validity of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986.

- The Court upheld the Act but ruled that limiting a divorced Muslim woman’s right to maintenance only for the ‘Iddat’ period would be discriminatory.

- The judgment ensured that Muslim women receive ‘reasonable and fair provision and maintenance’ beyond the iddat period, preventing religious-based discrimination.

#2 Race

Discrimination based on race is unconstitutional under Article 15(1). India, being a diverse country with different ethnic groups, has seen instances of racial bias, especially against people from Northeast India and tribal communities.

Sanghar Umar Ramval v. State of Saurashtra (1952)

- A Saurashtra law required specific racial communities to report to the police daily.

- The Supreme Court struck down this law, ruling that mandating police reporting based on race alone was unconstitutional.

Criminal Law (Removal of Racial Discrimination) Act, 1949

- This Act was a landmark step toward eliminating racial discrimination, particularly abolishing colonial-era privileges enjoyed by Europeans and Americans under British rule in criminal law matters.

#3 Caste

Caste discrimination remains one of the most entrenched forms of social inequality in India. Article 15(1) prohibits caste-based discrimination, but due to historical injustices, special provisions under Article 15(4) allow affirmative action for Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs).

Ashok Kumar Thakur v. Union of India (2008)

- The Supreme Court ruled that caste and class often overlap, and caste can be considered a determining factor in identifying socially and educationally backward classes.

Balaji v. State of Mysore (1963)

- The Court held that caste alone cannot be the criterion for identifying backward classes. Economic and social factors should also be considered.

Rajendran v. State of Madras (1968)

- The Court clarified that if an entire caste is socially and educationally backward, reservation based on caste is valid under Article 15(4) and does not violate Article 15(1).

#4 Gender

Article 15(1) guarantees gender equality, preventing the State from discriminating against any individual based on sex.

However, Article 15(3) allows the State to make special provisions for women and children to promote equality.

Rani Raj Rajeshwari v. State of UP (1954)

- A provision under the UP Courts of Wards Act (1879) allowed the State to declare male proprietors incapable of managing property only under specific conditions, whereas female proprietors could be declared incapable on any ground, without a chance to defend themselves.

- The Court struck down the provision as unconstitutional under Article 15(1).

Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018)

- The Supreme Court decriminalized homosexuality by striking down Section 377 of the IPC.

- Justice DY Chandrachud held that discrimination based on sexual orientation amounts to gender-based discrimination under Article 15(1).

#5 Place of Birth

Discrimination based on place of birth violates Article 15(1) and is closely linked to Article 16(2), which prohibits employment discrimination based on place of birth.

However, certain State laws provide domicile-based reservations in education and employment, which remain a contentious issue.

State v. Husein (1951)

- Section 27(2A) of the Bombay Police Act, 1951, imposed restrictions on persons born outside Greater Bombay.

- The Court struck it down, ruling that it discriminated against citizens based on place of birth, violating Article 15(1).

Clause 2: Restrictions on Citizens and Public Access

Clause 2 extends the prohibition of discrimination beyond State action. It states:

“No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them, be subject to any disability, liability, restriction or condition with regard to

(a) Access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and places of public entertainment; or

(b) The use of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, roads and places of public resort maintained wholly or partly out of State funds or dedicated to the use of the general public.”

The language here is deliberately broad. By using the term “shops” in a generic sense, the framers intended to include not only traditional retail establishments but any commercial or public facility that offers goods or services to the public.

This broad interpretation has been pivotal in cases where discriminatory practices in the private sector have been challenged under Article 15.

For instance, in a much-discussed judgment, the Court observed:

“The term ‘shop’ is not to be confined to the conventional retail establishment but should be interpreted in its widest possible sense, encompassing any place where goods or services are offered to the public.”

(Derived from judicial interpretations and Constituent debates)

Clause (2) of Article 15 extends beyond just the State—it also applies to private individuals who control access to public places. However, this provision isn’t self-executing, meaning it remains ineffective unless supported by legislation.

The Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955, does make violations of Article 15(2) punishable, but only in cases of discrimination based on untouchability.

This raises a crucial question: What happens if someone is denied access to public wells, restaurants, or other public facilities based on race, caste, or gender? The law remains unclear on this point, leaving room for ambiguity in enforcement.

Another challenge lies in seeking legal recourse. Filing a case under Article 32, which allows citizens to move the Supreme Court for rights violations, is often ineffective in such scenarios.

This is because the Court has consistently held that Article 32 remedies apply only against State action, not private individuals.

As a result, cases of discrimination in privately managed public spaces continue to fall into a legal gray area, making enforcement of Article 15(2) incomplete.

Clause 3: Special Provisions for Women and Children

Clause 3 provides the State with the authority to make special provisions for the advancement of women and children:

“Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any special provision for women and children.”

This clause acknowledges the historical and social disadvantages faced by women and children in India. Rather than merely prohibiting discrimination, it empowers the State to take affirmative steps to uplift these groups.

Such measures have included educational scholarships, reservation in public employment, and other welfare schemes.

The underlying rationale is that, given centuries of subjugation and social prejudice, merely ensuring formal equality is insufficient. Positive discrimination is necessary to level the playing field and enable true social integration.

Legal Precedents Explaining Article 15(3)

To understand the scope of Article 15(3), it’s essential to look at landmark cases where the courts have interpreted and applied this provision in real-life contexts.

1. Yusuf Abdul Aziz v. State of Bombay (1954)

In this case, the appellant, Yusuf Abdul Aziz, was charged under Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalizes adultery. The central issue was whether Section 497 violated Articles 14 and 15, which guarantee equality and prohibit discrimination.

Section 497 allowed only men to be prosecuted for adultery, while women could not be held criminally liable as abettors. The appellant argued that this provision discriminated against women and was thus unconstitutional.

However, the court ruled that Article 15(3) allows the State to enact laws that protect women specifically, such as those that prevent exploitation or promote gender equality.

The court emphasized that while laws may treat women differently to protect them, this does not amount to discrimination.

Furthermore, the appellant in this case was not a citizen of India, so he could not invoke Articles 14 or 15 to challenge the law. Therefore, his appeal was dismissed.

2. Paramjit Singh v. State of Punjab (2009)

This case revolved around the issue of election eligibility in a Panchayat election reserved for Scheduled Caste women.

The petitioner challenged the election of a woman who was elected as Sarpanch, arguing that the seat was reserved for women of Scheduled Castes only.

The court held that any individual from the Scheduled Caste category could contest the seat, regardless of gender.

The ruling clarified that special provisions for women in the context of reservations should not be confused with discriminatory provisions.

Women, particularly those from marginalized groups like Scheduled Castes, are entitled to be beneficiaries of such provisions for achieving greater representation and empowerment.

3. Govt. of A.P. v. P.B. Vijaykumar (1995)

In this case, the Andhra Pradesh government had enacted a rule that mandated preference for women in certain government posts if the candidates were equally qualified as men. The provision set a 30% reservation for women in specific posts, particularly in direct recruitment.

The Supreme Court upheld the provision, emphasizing that Article 15(3) allows such affirmative actions to promote equality.

By reserving posts for women, the law aimed to overcome the barriers women face in competing with men in various fields, especially in a society where gender-based discrimination is rampant.

The court’s ruling reinforced the idea that laws favoring women are not only constitutionally permissible but also necessary for societal advancement.

4. Vijay Lakshmi v. Punjab University (2003)

In this case, the issue at hand was the reservation of posts for women in women’s colleges and hostels. The Supreme Court upheld the reservations, citing Article 15(3).

The court stated that special provisions for women, especially in education and employment, are vital for achieving gender equality, as women have historically faced disadvantages in these spheres.

The judgment underscored the importance of institutional support for women, such as reserved seats in educational institutions, which help provide equal opportunities for women in a society where they have traditionally been marginalized.

5. Girdhar v. State of Uttar Pradesh (1953)

This case involved a male petitioner who challenged the law under Section 354 of the Indian Penal Code, which deals with assault to outrage the modesty of a woman. The petitioner argued that no such law existed for men, and that this was discriminatory.

However, the court rejected the claim, stating that laws such as Section 354 were enacted to protect women who have historically been vulnerable to gender-based violence.

The judgment reaffirmed that such laws are constitutionally valid under Article 15(3), as they are special provisions designed to protect women.

6. Choki v. State of Rajasthan (1957)

In this case, Mt. Choki was denied bail after she was accused of conspiring to murder her child. She appealed for bail on the grounds that she had a young child dependent on her.

The Supreme Court, citing Article 15(3), granted her bail, acknowledging the need for leniency in cases involving women with dependent children.

This case exemplified how Article 15(3) can be invoked to provide special protections for women in difficult circumstances.

7. Vishaka & Ors v. State of Rajasthan (1997)

One of the most significant cases regarding women’s rights, this case dealt with the issue of sexual harassment in the workplace.

The Supreme Court formulated the Vishakha Guidelines, which laid down specific steps that employers must take to prevent sexual harassment.

These guidelines became a cornerstone for India’s laws on sexual harassment, as they highlighted the special need for protecting women from such violence and discrimination.

The Vishakha Guidelines are an important legal advancement in ensuring a safe working environment for women. They also illustrate how Article 15(3) can be interpreted to create protective mechanisms specifically addressing gender-based violence.

Why Special Provisions for Women and Children Are Necessary

The provisions made under Article 15(3) are not arbitrary but are necessary for leveling the playing field, especially given the historical inequalities faced by women and children in Indian society.

Laws like the Maternity Benefit Act, 1961, the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act, 1994, and the Right to Education Act, 2009, provide essential benefits to women and children, aiming to ensure equal opportunities and protection in areas where they have been traditionally disadvantaged.

Examples of Special Provisions for Women and Children

- Right to Free and Compulsory Education: The Right to Education Act, 2009 mandates free education for children up to the age of 14. This provision particularly benefits girls who have historically had limited access to education.

- Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act, 2017: This law extends maternity leave for women working in both the public and private sectors, acknowledging the need to protect the health and well-being of working mothers.

- Reservations in Education and Employment: Various state and national-level reservations in educational institutions and government jobs for women, SC/ST, and OBC communities aim to reduce inequality and improve access to resources.

Can Laws Favoring Women Be Considered Discriminatory?

While some might argue that laws favoring women are discriminatory towards men, it is essential to understand that affirmative action is a necessary tool for correcting historical and structural imbalances.

Laws that protect women from violence, ensure equal opportunities, and provide specific protections are not discriminatory—they are remedies designed to ensure equality.

As exemplified in cases such as Girdhar v. State and Choki v. State of Rajasthan, the law’s focus on women’s protection and support does not amount to discrimination against men but rather recognizes the unique challenges faced by women due to historical biases and violence.

Clause 4: A Special Provision for Backward Classes

Article 15(4) of the Indian Constitution is a significant provision that permits the State to make special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward classes, as well as Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

This clause was added to the Constitution through the Constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951, in response to critical developments in post-independence India.

These developments brought to light the need for provisions that would enable the government to aid those communities that were historically disadvantaged and continue to face systemic barriers to education, employment, and social inclusion.

The introduction of Clause 4 sought to strike a balance between promoting equality while acknowledging the socio-economic reality faced by certain sections of society. Let’s explore how this provision functions and its impact, with the help of landmark cases that shaped its interpretation.

Historical Context and Rationale Behind Article 15(4)

The need for Article 15(4) arose from two major judicial cases that highlighted the limitations of the legal framework at that time.

These cases reflected the difficulties in providing a fair and just system of education and employment for backward classes without violating the principle of equality.

1. State of Madras v. Srimathi Champakam (1951)

In the State of Madras v. Srimathi Champakam (1951) case, the State of Madras issued an order that allocated seats in medical and engineering colleges based on the student’s caste.

The reservation of seats was based on caste and not merit, which the Court held to be unconstitutional. It was determined that such an allocation violated Article 15(1), which forbids discrimination based on caste, as it did not align with the principle of merit.

This case highlighted the necessity for the Constitution to include provisions that could allow for special provisions to help backward classes without infringing on the principle of equality.

2. Jagwant Kaur v. State of Maharashtra (1952)

The second motivating factor was the Jagwant Kaur v. State of Maharashtra (1952) case, in which the construction of a colony exclusively for Harijans (Dalits) was challenged as discriminatory.

The Court observed that while providing spaces for marginalized communities was essential, it should not lead to perpetuating caste-based segregation.

This case further emphasized the need for legal safeguards to protect the social and educational advancement of disadvantaged communities, which led to the introduction of Clause 4 in Article 15.

Special Provisions for Backward Classes

Article 15(4) allows the State to make special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward citizens, which includes affirmative actions such as reservations in educational institutions and government jobs.

The provision was crucial to uplift communities such as the SCs, STs, and OBCs, who were traditionally marginalized and faced significant barriers to accessing equal opportunities.

Components of Article 15(4)

- Special provisions for backward classes: These provisions aim to provide opportunities for education, employment, and social mobility to groups historically denied access to them. These provisions can include reservations or other affirmative action measures.

- Alignment with Article 29(2): The provision ensures that no citizen is discriminated against in admissions to educational institutions or receiving state funds based on religion, race, caste, or language, except where specific provisions have been made for backward classes.

Landmark Cases Interpreting Article 15(4)

Several judicial decisions have shaped the application and interpretation of Article 15(4), particularly in defining what constitutes a “backward class” and whether caste alone can justify affirmative action.

1. A. Periakaruppan v. State of Tamil Nadu (1971)

In A. Periakaruppan v. State of Tamil Nadu (1971), the Court made it clear that caste-based reservations must be coupled with evidence of social and educational backwardness. It held that classifying backward classes solely based on caste would violate the provisions of Article 15(4).

The judgment emphasized that any provision should consider both social and educational backwardness, not just caste identity. The Court argued that improving the conditions of the backward classes should be the primary objective of the reservation policy.

2. Balaji v. State of Mysore (1963)

The Balaji v. State of Mysore (1963) case was pivotal in determining the extent to which reservations could be made. The Mysore Government had decided to reserve 68% of seats for backward classes in medical and engineering colleges, leaving only 32% for students based on merit.

The Court found this to be unconstitutional, arguing that the reservations could not exceed 50%, as this would violate the principle of equality.

The judgment underlined that the allocation of seats should be done fairly, ensuring that merit is not compromised excessively.

The Court also highlighted that Article 15(4) does not justify exclusive provisions based solely on caste, but rather on the class’ social and educational status.

3. State of Andhra Pradesh v. USV Balaram (1972)

In State of Andhra Pradesh v. USV Balaram (1972), the Court clarified that caste alone is not a sufficient criterion for defining backwardness.

It ruled that the term “backward class” encompasses both social and educational backwardness.

The Evolution of Reservations and Their Constitutional Boundaries

One of the major issues regarding Article 15(4) is the extent to which the State can make provisions for backward classes. Over time, the Supreme Court has established certain boundaries for such provisions.

Reservations Beyond 50%?

One of the most critical limits placed by the Supreme Court on reservations is that they should not exceed 50% of the available seats in educational institutions or government jobs.

This limit ensures that merit is not entirely compromised and that the policy of reservations remains fair and just.

For instance, in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992), the Supreme Court reaffirmed the 50% cap on reservations, ensuring that this principle remains intact.

Focus on Socio-Economic Empowerment

The primary goal of Article 15(4) is to provide socio-economic empowerment to disadvantaged groups. This means that, while caste can be a factor in identifying backward classes, it is not the sole factor.

The focus should always be on improving the conditions of the people in question, providing them with better opportunities for education, employment, and societal participation.

The Future of Article 15(4)

The interpretation of Article 15(4) has evolved significantly over the decades. As social and educational conditions improve, the list of backward classes must be periodically updated to reflect current realities.

In the future, there may be a need to re-evaluate which communities need reservations and ensure that the focus remains on those truly requiring special provisions.

It is also essential that the government ensure proper monitoring and evaluation of these provisions, to prevent misuse and ensure that reservations are benefiting those who truly need them.

With the advancement of technology and improved access to education and social services, the need for reservations may change, and legal frameworks will need to adapt accordingly.

Clause 5: Special Provisions for Backward Classes and SCs/STs in Educational Institutions

Article 15(5) was introduced through the Constitution (Ninety-Third Amendment) Act of 2005 to further the cause of social justice by enabling the government to make special provisions for the educational advancement of socially and educationally backward classes, including Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

This clause clarifies that while Article 15 prohibits discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth, it allows exceptions for creating provisions that benefit these disadvantaged groups.

These provisions, especially in the context of educational institutions, can apply to both public and private institutions, irrespective of whether they are funded by the state or not. However, minority educational institutions, as defined under Article 30(1), are excluded from this clause.

One of the significant features of Article 15(5) is its focus on affirmative action in education, where reserved seats can be set aside for SCs, STs, and other backward classes (OBCs).

This provision was seen as a necessary measure to bridge the gap in access to education for these historically marginalized groups. The goal is to provide them with equal opportunities to participate in higher education, which remains crucial for social mobility.

Landmark Case: Ashok Kumar Thakur v. Union of India (2008)

In this case, the Supreme Court upheld the Constitution (Ninety-Third Amendment) Act that inserted Clause 5 of Article 15.

The Court clarified that the provision was applicable to State-maintained and State-aided institutions but also set a critical boundary.

It ruled that backward classes falling under the “creamy layer” (the relatively wealthier sections of backward classes) would not be eligible for the benefits of this amendment.

The creamy layer concept was emphasized to ensure that the reservation system serves its intended purpose of uplifting those who are genuinely disadvantaged, not those who have already moved beyond the economic threshold of backwardness.

The Court further held that any reservation policy that fails to adhere to the test of reasonableness might face judicial scrutiny.

In this context, the reasonableness test ensures that caste-based reservation doesn’t become inherently discriminatory over time, especially as society progresses toward greater social equality.

Thus, while the primary aim of Article 15(5) is to uplift marginalized sections, the principle of non-discrimination and meritocracy remains integral to its application.

The focus, therefore, is to eliminate caste-based discrimination, not perpetuate it, making judicial review an essential safeguard.

Clause 6: Special Provisions for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS)

The Constitution (One Hundred and Third Amendment) Act of 2019 introduced Clause 6 into Article 15, which empowers the government to make special provisions for the advancement of economically weaker sections (EWS) of citizens.

This includes reserving a portion of seats in educational institutions and government jobs for EWS individuals.

The amendment specifically allows for 10% reservation in educational institutions for the economically disadvantaged, with provisions extending to both aided and unaided private institutions, except for minority educational institutions under Article 30(1).

This marked a significant shift in India’s reservation system, as it moved beyond caste-based reservations to include economic backwardness as a criterion for affirmative action.

Landmark Case: Janhit Abhiyan v. Union of India (2022)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment in Janhit Abhiyan v. Union of India (2022), upheld the 103rd Constitutional Amendment with a 3-2 majority. The Court reinforced the idea that reservations based on economic criteria do not violate the Constitution’s principle of equality under Article 14.

The judgment emphasized that this form of affirmative action was constitutionally valid and did not violate the principles of equality or non-discrimination, as long as it was based on economic disadvantage and not caste.

In this way, the Court recognized that economic disparities, much like social backwardness, also merit targeted intervention to promote equality of opportunity.

While the reservation system aimed at caste-based upliftment continues to play a critical role in Indian society, Clause 6 of Article 15 introduces a new dimension to the reservation debate: a focus on economic class.

Intersection with Article 29(2): Equal Access to Educational Institutions

Article 29(2), which is closely linked with Article 15(4), reinforces the right to non-discriminatory access to educational institutions.

It states that no citizen shall be denied admission to any educational institution funded by the state on the grounds of religion, race, caste, or language.

Judicial Interpretation and Landmark Cases

Early Interpretations and the Role of Ambedkar

B.R. Ambedkar’s influence on the interpretation of Article 15 cannot be overstated. As the chairman of the Drafting Committee, Ambedkar envisioned a Constitution that would be a “living document,” capable of evolving with society’s needs.

His insistence on broad language has allowed Article 15 to be interpreted in a manner that not only prohibits overt discrimination but also addresses subtler, systemic inequalities.

In the early years after independence, courts focused on the literal meaning of the text. However, as societal contexts changed, the judiciary began to adopt a purposive approach. One of the earliest cases to demonstrate this evolution was the interpretation of discrimination in access to public facilities.

The courts emphasized that the effect of any policy must be measured by its impact on the dignity and rights of citizens, rather than merely its stated intent.

Air India v. Nergesh Meerza and Beyond

Several landmark judgments have shaped the contours of Article 15. One of the most cited is Air India v. Nergesh Meerza (1981), wherein the Supreme Court held that discrimination based solely on sex, when accompanied by other factors, still fell within the ambit of Article 15.

In this case, the Court underscored that even if a law or practice is justified on non-discriminatory grounds, if its net effect is to disadvantage a protected class, it must be struck down or read down.

Another significant case is Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018). In this historic judgment, the Supreme Court decriminalized consensual sexual conduct between adults by interpreting the prohibition of discrimination in Article 15 to extend to sexual orientation and gender identity.

The Court’s reasoning was that discrimination based on stereotypes about what constitutes “proper” sexual behavior was antithetical to the spirit of equality enshrined in the Constitution.

A noteworthy observation from the Navtej Singh Johar judgment was:

“Discrimination, however subtle, when rooted in stereotypical notions of sexuality, must be challenged in the light of the transformative vision of our Constitution.”

(Paraphrased from the Court’s concurring opinion)

This judgment not only extended the protection of Article 15 to LGBTQ+ individuals but also set a precedent for future cases dealing with intersectional discrimination.

Intersectionality and the Evolving Meaning of “Sex”

One of the more complex debates in the judicial history of Article 15 is the interpretation of the word “sex.”

Originally intended to prevent discrimination against women, over time the term has been reinterpreted to encompass broader notions of gender identity and sexual orientation.

Critics initially argued that such an expansion diluted the original intent of the provision; however, successive judgments have clarified that discrimination based on stereotypes—whether related to sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation—is incompatible with the constitutional guarantee of equality.

In a series of progressive judgments, the Supreme Court held that:

“Equality under the law must be inclusive; it is not sufficient to merely remove overt discrimination when systemic biases continue to undermine the dignity of individuals.”

(A summative observation reflecting the Court’s evolving stance)

This intersectional approach has allowed the judiciary to address cases where multiple protected characteristics intersect—ensuring that the rights of individuals who face compounded discrimination are safeguarded.

Is Reservation a Justified System of Positive Discrimination Under the Indian Constitution?

The Indian Constitution, while ensuring equality under Article 15(1), acknowledges that in certain situations, specific groups may require assistance to ensure they are on a level playing field.

This recognition of historical and systemic disadvantages faced by certain communities has led to the introduction of reservation provisions in the Constitution.

These reservations are based on Article 15(3), (4), and (5), which offer exceptions to the general rule of non-discrimination.

The Concept of “Protective Discrimination” (Positive Discrimination)

The provisions under Article 15(3), (4), and (5), while exceptions to the non-discrimination rule, do not promote discrimination in the conventional sense.

Instead, they aim to correct historical imbalances and empower marginalized communities by ensuring they receive equal opportunities in various spheres of life. This principle is often referred to as “Protective Discrimination” or “Positive Discrimination.”

This policy seeks to elevate the status of historically disadvantaged and underprivileged sections of society, including Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and even women and children.

It is a mechanism intended to provide these groups with a platform to compete on equal footing with the more privileged sections of society.

Reservations and Equal Opportunity: Does it Create an Unfair Advantage?

One common argument against reservation is whether it creates an unfair advantage for underprivileged groups, especially in skill-based fields such as medicine and the armed forces, where competence and qualifications are critical.

Critics argue that reservation might lead to unqualified individuals entering highly specialized areas, potentially undermining the system’s efficacy.

However, such an argument overlooks the social realities faced by individuals from underprivileged backgrounds. Take, for example, Ramu, a boy from a disadvantaged family, who has no guidance or resources for education.

Despite his inherent capabilities, he faces significant systemic obstacles that make it challenging to compete with someone like Vicky, who belongs to a well-off family with access to resources and mentors.

In such scenarios, reservation plays a crucial role in ensuring that Ramu, despite his lack of resources, can have an opportunity to access education and career paths that are otherwise monopolized by the privileged classes.

Reservation in Medical Colleges

One of the most debated areas for reservation is in professional education, particularly in fields like medicine.

The argument here is whether the reservation system might allow underprivileged students to enter highly specialized fields without meeting the academic standards of their peers.

In Ajay Kumar v. State of Bihar (2019), the issue was raised about the permissibility of reservation in postgraduate medical courses under Article 15(4). The appellants argued that Article 15(4) doesn’t explicitly allow for reservation in educational institutions.

The court, however, rejected this argument, noting that special provisions, including reservation, are permissible under Article 15(4) to promote the welfare of backward classes, including those in higher education.

This judgment reinforces the idea that reservation is not an unjustified advantage but a necessary tool to level the playing field and ensure that every section of society has equal access to opportunities, including in the medical profession.

Reservations Based on Domicile

While reservation based on caste or backwardness is widely accepted, reservation on the basis of domicile remains a controversial and less-discussed issue. The idea of offering benefits to local residents or ethnic groups against migrants from other regions is sometimes perceived as unjust discrimination.

However, the Constitution does not explicitly prohibit reservation based on domicile. In fact, the place of birth is not an explicit ground for discrimination under Article 15.

It’s important to note that domicile refers to the place where a person resides, which may be different from their birthplace.

Therefore, reservations based on domicile do not necessarily violate the principle of non-discrimination based on place of birth, as these categories are distinct.

The Concept of Reservation Within Reservation

A growing phenomenon in India is the concept of reservation within reservation, which aims to address further inequalities within already reserved communities.

In other words, it focuses on ensuring that the most disadvantaged within a disadvantaged community are also given adequate opportunities.

For instance, certain sections within the Scheduled Castes (SCs), like the Madiga community, face significant social and economic challenges, despite being part of the SC category.

To address this, states like Andhra Pradesh have implemented a sub-reservation policy within the SC category, ensuring that even these communities benefit from affirmative action.

Similarly, the Maratha community in Maharashtra and the Jat community in Haryana have demanded and received OBC reservations in certain regions.

Is Reservation for Specific Groups Fair?

There is an ongoing debate about whether reservation continues to serve its intended purpose or if it has lost its relevance over time.

Some argue that reservation is essential to ensure that marginalized groups receive equal opportunities in education, employment, and representation.

Others believe that it perpetuates divisions within society and may foster a sense of entitlement or dependence on affirmative action.

The argument is not about whether the underprivileged deserve a chance, but rather about how reservation is implemented, and whether it focuses on social and economic backwardness rather than just caste.

Implementing reservation more effectively requires a focus on economic disadvantages, skills development, and addressing educational gaps across all communities.

What is Area-Wise Reservation Under Article 371 and the Special Provisions for States?

The Constitution of India contains provisions for “special provisions” for certain states, recognizing their unique cultural, social, and geographical needs.

These provisions allow for the formulation of area-specific reservation policies, ensuring local populations benefit from opportunities in public employment and education.

These provisions address the distinct challenges faced by residents in these regions, aiming to promote inclusivity and equitable access to resources.

Here is a breakdown of the Articles in the Constitution that grant special provisions for different states in India:

Article 371

This Article applies to the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat. It lays down the framework for ensuring that local residents have access to public opportunities without being disadvantaged by factors such as migration from other parts of India.

Article 371A

This Article addresses special provisions for the state of Nagaland. It ensures that the state’s unique cultural identity and traditions are preserved, especially in matters related to the land, local governance, and public affairs.

Article 371B

Special provisions under Article 371B are meant for Assam. This provision focuses on the socio-economic development of the state, considering its distinct ethnic and cultural composition.

Article 371C

Manipur, being a state with diverse ethnic communities, benefits from special provisions under Article 371C. This ensures that its local residents have an equal opportunity for education, employment, and participation in public affairs, respecting the region’s unique needs.

Article 371D

For Andhra Pradesh, Article 371D allows the formulation of policies that promote local development and ensure that the public sector benefits are accessible to the people of the state. This provision is particularly helpful in addressing the needs of different regions within the state, fostering balanced growth.

Article 371F

Sikkim, with its distinct identity and demographic, benefits from special provisions under Article 371F. These provisions are designed to protect the cultural and social fabric of the state while offering local people opportunities in various fields.

Article 371G

Article 371G addresses the state of Mizoram. The primary focus of this provision is to safeguard the unique traditions, culture, and rights of Mizo people while ensuring that their educational and employment opportunities are protected.

Article 371H

Arunachal Pradesh has special provisions under Article 371H, which are tailored to its socio-cultural dynamics. This provision ensures that the state’s local population has access to educational opportunities and government jobs in line with the region’s needs.

Article 371I

The state of Goa benefits from special provisions under Article 371I, which allow for the protection and promotion of the local culture and population in matters of public employment and education.

Article 371J

Article 371J caters to the state of Karnataka. This provision ensures that local residents have fair access to public opportunities and that the state’s distinct regional needs are taken into account in government policies.

Advancement of Backward Classes: Article 15(4)

Article 15(4) of the Indian Constitution allows the state to make special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward classes, as well as Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

This provision empowers the state to enact laws or initiatives that facilitate the upliftment of historically marginalized communities, ensuring that they have equal opportunities in society, particularly in education and public employment.

Is Article 15(4) a Fundamental Right?

While Article 15(4) belongs to Part III of the Constitution, which deals with fundamental rights, the question arises: does it constitute a fundamental right itself? The answer is complex.

Not every provision in Part III automatically qualifies as a fundamental right. Some provisions are aimed at detailing or enforcing other rights, while others lay down exceptions or clarifications.

Article 15(4) stands out as an exception within the broader right to equality enshrined in Articles 14 to 18, which guarantee equality before the law.

While Article 14 ensures equality for all and Article 16 mandates equal access to public sector employment, Article 15(4) acknowledges the need for remedial measures to address systemic social and educational disadvantages that certain groups face.

Thus, Article 15(4) doesn’t contradict the principle of equality but redefines it by promoting substantive equality. It recognizes that identical treatment may not be sufficient to achieve actual equality, especially for historically oppressed groups.

Affirmative Action and the Right to Equality

In understanding whether Article 15(4) is a fundamental right, it’s helpful to explore the concept of affirmative action.

Article 15(4) permits the state to make provisions for backward classes to enable them to catch up with others in areas like education, employment, and social standing.

This contrasts with the principle of formal equality under Article 14, which calls for identical treatment for all.

But substantive equality—the idea that individuals or groups with unequal starting points may need different treatment to level the playing field—justifies the differential treatment under Article 15(4).

This approach is not an infringement of equality but rather a way to give everyone a fair chance at success.

Renowned philosopher Ronald Dworkin highlights this distinction between “equal treatment” and “treating as equal.”

According to Dworkin, “equal treatment” implies giving everyone the same treatment, while “treating as equal” involves considering their individual circumstances to ensure fairness.

Dworkin suggests that equal concern is more important than identical treatment.

In this context, Article 15(4) is in line with Dworkin’s theory of equality of concern. It permits the state to provide unequal treatment, but only when it is to ensure that socially and educationally backward classes are not left behind.

For instance, providing special scholarships, reservations in educational institutions, or job quotas to SCs, STs, and OBCs is not discriminatory, but rather a corrective measure aimed at achieving real equality.

Discrimination and Special Provisions

Article 15(4) exists as a counterpoint to Article 15(1), which prohibits discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. However, it is crucial to note that discrimination in this context refers to prejudice or disrespect.

The state is not barred from treating citizens differently; it is prohibited from treating them in a way that implies inferiority or disrespect based on their identity.

Special provisions under Article 15(4) are meant to aid backward classes in achieving parity with more privileged groups, and these provisions are a response to systemic inequality, not an expression of contempt.

Thus, such measures are in harmony with the overarching principle of equality in the Constitution, as long as they are designed to uplift rather than diminish.

Article 15(4) vs. Article 29(2)

Another important distinction is between Article 15(4) and Article 29(2). While Article 15(1) and Article 29(2) prohibit discriminatory practices by the state, Article 15(4) enables the state to adopt measures that may appear discriminatory on the surface but are designed to correct deep-rooted social imbalances.

For example, reservation policies or caste-based quotas may seem to create a distinction based on caste, but their ultimate goal is to address historical disadvantages faced by certain groups.

These measures are not about creating inequality but about achieving substantive equality, where everyone is given the tools to succeed.

The Importance of Article 15(4)

By permitting affirmative action, Article 15(4) serves as a critical tool in addressing inequalities that continue to affect backward classes, SCs, and STs in India.

Without these provisions, it would be extremely challenging to dismantle the deep-seated social hierarchies that persist, despite legal reforms.

At its core, Article 15(4) reflects the Constitution’s commitment to social justice, aiming to break the cycles of poverty and marginalization.

The state’s ability to make special provisions for these communities is integral to the larger goal of building an inclusive society, where every citizen has a fair opportunity to thrive.

The Amendment and its Impact on Reservation Policies in India

The Mandal Commission Report, which recommended a system of reservations for the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs), has been a pivotal document in shaping India’s social justice landscape.

The Commission proposed that a substantial portion of educational and government service seats—nearly 50%—should be allocated to these groups, as they made up around 70% of the Indian population.

Following this, the landmark Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992) ruling by the Supreme Court validated these provisions, affirming the constitutional basis for caste-based reservations. This significantly improved the status of these historically marginalized communities.

As the need for social and economic upliftment of the backward classes became more pronounced, the Indian government was compelled to create more inclusive policies aimed at improving the economic conditions of those who fall under the ‘other’ category.

This led to the Constitution (103rd Amendment) Act, 2019, which introduced a 10% reservation for economically backward sections (EWS) in the general category, specifically in educational institutions and government jobs.

The 103rd Amendment, however, stirred a heated debate. Critics argued that the amendment violated the basic structure doctrine of the Indian Constitution, which limits the scope of constitutional amendments.

According to this doctrine, amendments cannot alter the core principles or essential features of the Constitution.

The term basic structure was first articulated in the Sajjan Singh v. State of Rajasthan (1964) case, which questioned whether changes to the Constitution could be considered mere amendments or if they would effectively rewrite the Constitution.

This inquiry was crucial, as it laid the groundwork for future interpretations of the Constitution’s rigidity and adaptability.

The matter was subsequently addressed in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), where the Supreme Court famously declared that any amendment that alters the basic structure of the Constitution is invalid.

Justice Sikri, in the judgment, emphasized that certain essential features—such as democracy, secularism, republicanism, and equality—cannot be compromised. This case set the precedent for evaluating the constitutionality of amendments, ensuring that any changes do not undermine the core principles of the Constitution.

Following Kesavananda Bharati, several other judgments, including Indira Nehru Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975) and Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India (1980), continued to uphold the basic structure doctrine.

The principle was further reinforced in M. Nagaraj v. Union of India (2006), which introduced the “twin test”—the width test and the identity test. These tests serve to examine whether an amendment impacts the Constitution’s basic features or alters its identity.

- The Width Test: This test assesses the extent of the amendment’s effect on the Constitution’s structure. If the amendment changes or undermines essential principles such as justice, democracy, and secularism, it may be considered invalid. The width test scrutinizes the broader consequences of any constitutional change.

- The Identity Test: This test determines whether the amendment alters the core identity of the Constitution. It focuses on whether the Constitution’s identity and fundamental values remain intact after the amendment. If an amendment significantly modifies these principles, it may be deemed unconstitutional.

The 103rd Amendment Act, 2019, which introduced reservations for the economically weaker sections (EWS) within the general category, faced questions on whether it violated these principles.

The legislation’s defenders argue that it is a necessary step to promote social and economic justice and to ensure that the benefits of affirmative action reach those who are economically deprived, regardless of their caste.

However, critics contend that by introducing economic criteria for reservations, the amendment could potentially blur the lines between social and economic criteria, which could be seen as altering the fundamental balance of the reservation system.

Thus, while the 103rd Amendment has led to significant policy changes, its compatibility with the Constitution’s basic structure will likely continue to be scrutinized. The introduction of economic criteria for reservations, specifically targeting the EWS in the general category, represents a shift in the way affirmative action is understood in India.

It challenges the established norms that reservations are primarily based on caste or community, raising questions about whether the amendment risks undermining the core intent of the Constitution’s provisions on equality and non-discrimination.

The Societal Impact of Article 15

Transforming Social Norms and Promoting Equality

Article 15 has played a critical role in transforming Indian society by challenging age-old discriminatory practices. For centuries, the caste system and patriarchal norms had relegated large segments of the population to subservient roles.

With the enactment of Article 15, a legal framework was established that not only prohibited such practices but also empowered marginalized communities.

Over the years, the implementation of Article 15 has been linked with several social reforms. Educational institutions, public services, and employment sectors have all witnessed policies aimed at redressing historical injustices.

For example, the introduction of reservation policies in higher education and public employment is one of the most visible manifestations of the State’s commitment to Article 15.

A fact often cited in academic and legal circles is that since the implementation of reservations, the enrollment of students from Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in higher education institutions has increased substantially.

Data from government reports reveal that in many states, the percentage of students from these groups has nearly doubled over the past few decades. Such trends underscore the transformative potential of Article 15 in reshaping social dynamics.

Affirmative Action and Reservations in Practice

The power to make special provisions under Article 15 is one of its most potent features. Reservations in education, employment, and political representation have been instituted as a means to level the playing field for communities that have suffered historic discrimination.

These affirmative action measures are not without controversy, but their impact on social mobility is undeniable.

For instance, several studies have shown that reservation policies have enabled members of historically disadvantaged communities to secure positions in government services and higher education.

One study noted that in states with robust reservation policies, the representation of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in higher education increased by over 50% within a generation.

Critics, however, argue that reservations may sometimes lead to reverse discrimination and create new forms of social division.

Nonetheless, most legal scholars and policymakers agree that in the context of India’s diverse and stratified society, affirmative action remains an essential tool for social justice. As one academic observed:

“Reservations are not a panacea, but they represent a critical step towards dismantling the entrenched systems of discrimination that have long plagued our society.”

(Quote adapted from scholarly debates on affirmative action)

The debate continues in public forums, academic circles, and the judiciary. Yet, the overall consensus is that affirmative action measures under Article 15 have been instrumental in driving progress.

Contemporary Debates and Criticisms

Critiques of the “Only” Doctrine

One recurring criticism of Article 15 centers on the phrase “on grounds only.” Early interpretations by some courts suggested that if discrimination occurred on the basis of a protected ground along with another factor, the action might not fall within the scope of Article 15.

This “only” doctrine was seen by many as overly restrictive and inadequate for addressing complex, multifaceted discrimination in modern society.

Feminist scholars and legal experts have argued that such a narrow interpretation fails to capture the realities of intersectional discrimination, where biases based on gender, race, and socioeconomic status often overlap.

Over time, the judiciary has moved away from a formalistic reading and adopted a more effect-based approach. This shift has allowed for a broader interpretation that considers the overall impact of discriminatory practices rather than merely their stated intent.

For example, in cases involving employment discrimination, the Court has held that even if a policy is justified on business grounds, if its effect disproportionately harms a particular group, it may still be challenged under Article 15.

This evolving jurisprudence has been hailed as a triumph for social justice, even as critics warn of the potential for judicial overreach.

Challenges in Implementation and Enforcement

Despite its lofty ideals, the practical enforcement of Article 15 faces several challenges. In many parts of India, social prejudices are deeply entrenched, and discriminatory practices persist despite legal prohibitions.

Enforcement mechanisms often rely on the willingness of individuals to come forward and challenge discriminatory practices—a process that can be fraught with personal and social risks.

Moreover, the effectiveness of affirmative action measures under Article 15 has been a subject of debate. While reservations have undeniably improved access to education and employment for marginalized groups, there is ongoing discussion about the need to update and refine these measures to reflect changing social realities.

Critics contend that the current system sometimes reinforces caste identities rather than dissolving them, calling for a more nuanced approach that addresses the root causes of inequality.

Another area of contention is the debate surrounding the 103rd Constitutional Amendment and the introduction of economic criteria in affirmative action.

While supporters argue that economic disadvantage is a critical factor that cuts across traditional social divisions, opponents fear that such measures may dilute the focus on historically oppressed groups.

As one noted legal commentator put it:

“The challenge lies not only in drafting progressive laws but in ensuring that these laws translate into real, measurable change on the ground.”

(Paraphrased from contemporary legal analysis on enforcement challenges)

These debates continue to shape both academic discourse and legislative policy, highlighting the dynamic and evolving nature of constitutional jurisprudence in India.

The Government’s Perspective on Reservation and Quotas

In the wake of the introduction of the 10% reservation for the Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) of society, various government officials have weighed in on the significance of this move.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi hailed the act as a landmark decision in the nation’s history, positioning it as a powerful mechanism to ensure justice for all sections of society.

According to him, the policy marks an important stride toward creating a more equitable society where all citizens, regardless of their socio-economic status, have access to opportunities.

Ex-Finance Minister Arun Jaitley further justified the move, arguing that equality should not merely be about treating everyone the same. He noted that individuals come from different backgrounds shaped by their birth and economic conditions.

As such, Jaitley explained, treating those who start from vastly unequal positions as equals would be inherently unjust. He asserted that those from disadvantaged economic backgrounds need targeted support to level the playing field.

On the matter of the 10% EWS quota, Jaitley highlighted an important distinction from traditional caste-based reservations.

While the Supreme Court has set a cap of 50% for caste-based quotas, the EWS reservation falls outside that cap, as it is rooted in economic status, not caste identity.

Thaawarchand Gehlot, former Union Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment, also addressed concerns about the legal standing of the EWS reservation.

He acknowledged that prior to this amendment, similar state-level laws for economic reservation had been struck down by courts on the grounds that the Constitution did not specifically recognize economic-based reservations.

However, with the constitutional amendment now making provisions for economic reservation, Gehlot argued that such laws were now solidly grounded in the Constitution, thus making them more likely to withstand judicial scrutiny.

Socially and Educationally Backward Classes (OBCs)

The concept of “socially and educationally backward classes” (SEBCs) finds its foundation in Article 15(4) of the Indian Constitution.

This provision was created to uplift the communities that have faced systemic oppression, social stigma, and a lack of opportunities for centuries.

While Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) have long been the focus of affirmative action policies, Other Backward Classes (OBCs) also form a significant part of this category.

OBCs, although not part of the SC/ST groups, have faced significant social and educational disadvantages, and thus are also entitled to benefits such as reservations to bridge these gaps.

By placing OBCs under this category, the government has extended its protective measures to a broader group of people who were historically marginalized and excluded from mainstream society.

The inclusion of OBCs under affirmative action programs continues to be crucial for fostering greater social mobility and reducing inequalities across India’s vast socio-economic spectrum.

The 50% Limit on Reservations

In the landmark Indira Sawhney v. Union of India (1993) case, the Supreme Court set a ceiling on the total amount of reservations that could be provided, establishing the critical benchmark of 50%.

The court ruled that exceeding this limit would compromise the principles of equality enshrined in the Constitution, as it would result in an overwhelming percentage of opportunities being reserved for certain groups, thereby depriving others of their fundamental right to equality and fair opportunity.

While the 50% limit stands as the guideline, the Court also recognized that there could be exceptional situations where this cap might be exceeded.

In such cases, the government must demonstrate a compelling need to uplift historically disadvantaged communities, particularly in regions with unique socio-economic challenges.

Exceeding the 50% Cap in Extraordinary Circumstances

While the 50% cap on reservations holds in most cases, some states have exceeded this threshold due to the extraordinary need to uplift specific backward classes.

In these cases, the respective state governments have taken the stance that the social and economic conditions of their populations warrant such action.

- Tamil Nadu stands as the most notable example, with a 69% reservation, 50% of which is allocated to OBCs. The state has consistently implemented higher reservation percentages in order to uplift its backward communities.

- Maharashtra follows closely behind with 52% reservation, while Telangana and Haryana have reservations of 62% and 67%, respectively. These states have justified their actions by citing the persistent socio-economic backwardness and need for greater affirmative measures to ensure equal access to opportunities for these marginalized groups.

Each of these states has demonstrated that, in the face of historic disadvantage, breaking the 50% barrier is crucial to achieving social and educational equity.

These deviations, though rare, reflect the government’s sensitivity to regional disparities and the evolving dynamics of socio-economic justice in a diverse country like India.

Recent Judgment on Same-Sex Marriage: Supriyo@Supriya Chakraborty & Anr. v. Union of India (2023)

In 2023, the Indian judiciary witnessed a landmark case involving the rights of same-sex couples. The petitioners, Supriyo@Supriya Chakraborty and another, sought a reform in the Special Marriage Act, 1954, to make it gender-neutral.

The Special Marriage Act, which was designed for couples who cannot marry under their respective personal laws, does not currently recognize same-sex marriages.

The petitioners argued that the Act’s refusal to allow same-sex couples to marry violated key fundamental rights, specifically Articles 14, 15, 19, 21, and 25 of the Constitution.

They requested that terms such as “husband” and “wife” be replaced with “party” or “spouse” to accommodate same-sex couples.

This case was heard by a constitutional bench consisting of five judges, who agreed that discrimination against same-sex couples must end. However, they couldn’t reach a consensus on granting same-sex couples the status of a “civil union” under Indian law.

The majority of the bench ruled that recognizing such unions could only be achieved through an Act of the Legislature.

In essence, they suggested that it was beyond the judiciary’s scope to create legal status for same-sex marriage and that it was the role of Parliament to pass such a law.

While the judges did not grant the petitioners’ demand for a legally recognized marriage, they did assert some fundamental rights for LGBTQ+ persons.

These rights included the right to gender identity, sexual orientation, the freedom to choose a partner, cohabit, and engage in physical and mental intimacy.

However, they clarified that the Constitution does not explicitly guarantee a right to marry for same-sex couples, limiting their claim to a civil union or marriage.

Interestingly, Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud referred to Article 15 in the judgment. He emphasized that Article 15 is concerned with protecting citizens from discrimination based on characteristics that define individual identity.

These characteristics—whether related to religion, race, caste, sex, or sexual orientation—must be interpreted in their historical and social context.

He argued that the concept of discrimination should not be viewed narrowly, as it often ignores the broader social and historical dimensions of identity.

The Interplay of Articles 14, 15, and 16:

The recent judgment also provides an opportunity to understand the connection between Articles 14, 15, and 16 of the Indian Constitution, which together embody the right to equality. These Articles work in tandem to provide constitutional protection against discrimination, but each also serves a specific function.

- Article 14 guarantees equality before the law and provides that no person shall be denied equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India. This Article, broadly speaking, applies to all persons, regardless of their citizenship status.

- Article 15 builds upon Article 14, offering specific protections against discrimination for Indian citizens on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth, or any other grounds. The key distinction here is that Article 15 applies exclusively to citizens of India, whereas Article 14 applies to all persons, citizens or not. This makes Article 15 more specific, especially as it addresses issues that have historically caused inequality in Indian society.