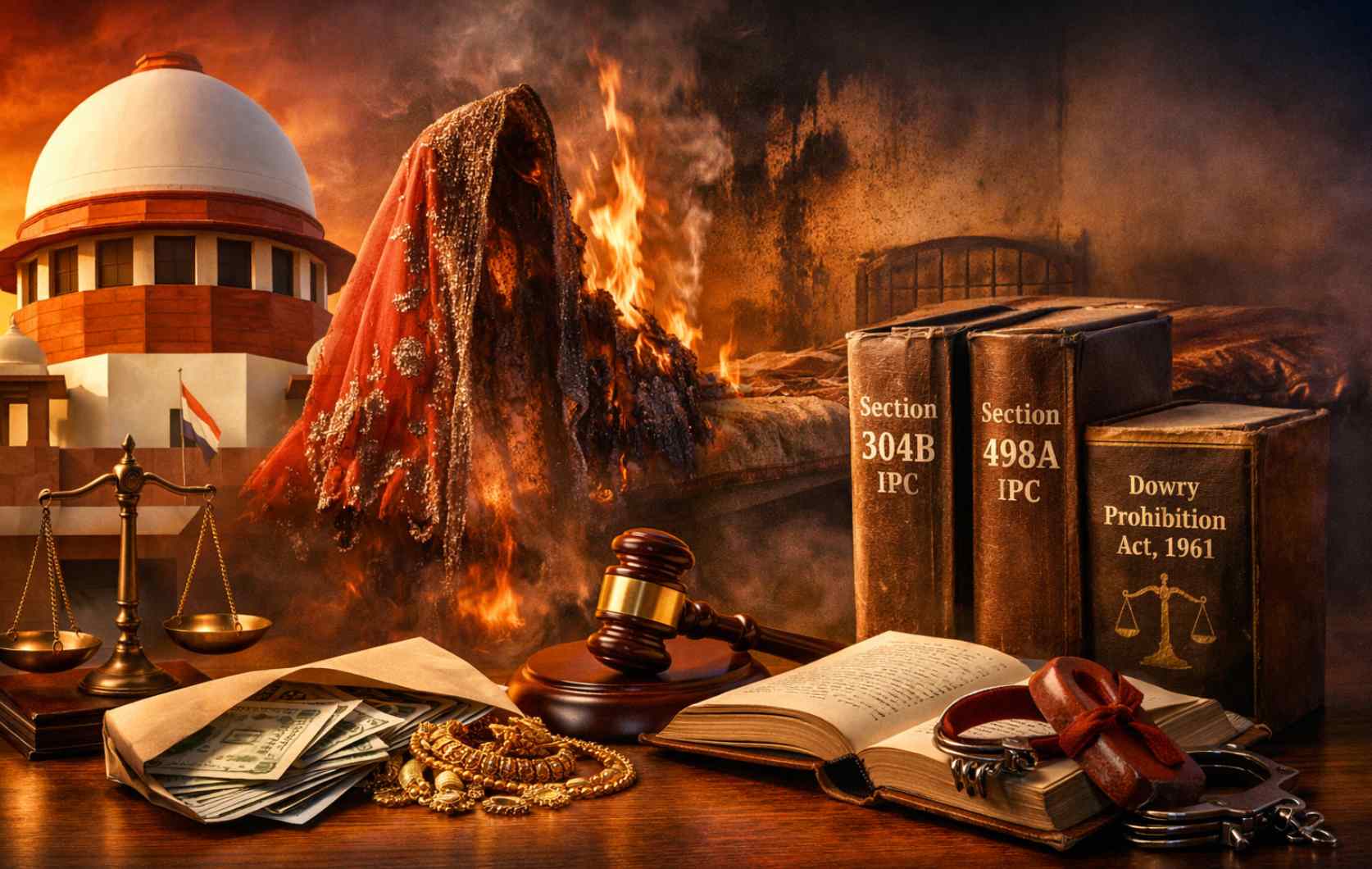

The Supreme Court of India has delivered a searing verdict in a dowry death case that has taken nearly 24 years to reach finality, restoring the conviction of a husband whose young wife was burned to death over unmet dowry demands.

The judgment not only overturns the acquittal granted by the Allahabad High Court but also stands out for its deeply human tone, sharp social commentary, and unflinching language on the commodification of women through marriage.

The case relates to the death of Nasrin, a woman barely in her twenties, who died within just over a year of her marriage.

The prosecution’s story, accepted by the trial court and now reaffirmed by the Supreme Court, was that Nasrin was subjected to repeated harassment and cruelty for dowry by her husband, Ajmal Beg, and his family.

The demands were neither vague nor symbolic. They were concrete and persistent: a coloured television, a motorcycle, and Rs. 15,000 in cash.

While recounting the tragedy, the Supreme Court used words that cut through legal abstraction and laid bare the human cost of dowry. The Court recorded:

“In this case, a young girl, barely of twenty, when she was sent away from the world of the living by way of a most heinous and painful death, met this unfortunate end simply because her parents did not have the material means and resources to satisfy the wants or the greed of her family by matrimony.”

In perhaps the most haunting line of the judgment, the Court added:

“A coloured television, a motorcycle and Rs. 15,000/- is all she was apparently worth of.”

These lines have already begun to resonate far beyond the courtroom, reflecting the brutal reality faced by countless women across the country.

Trial court findings and High Court acquittal

The Additional Sessions Judge at Bijnor, after examining eight prosecution witnesses, convicted Ajmal Beg and his mother Jamila Beg under Sections 304B and 498A of the Indian Penal Code and Sections 3 and 4 of the Dowry Prohibition Act.

Ajmal Beg was sentenced to life imprisonment for dowry death, along with additional sentences for cruelty and dowry demand. Jamila Beg was also convicted.

The trial court found that the deceased had been continuously harassed for dowry and that the demand had been reiterated just one day before her death.

It rejected the defence suggestion that Nasrin had committed suicide, noting that none of the accused made any effort to save her and that the extent of burning, including the quilt and roof, suggested that she had been deliberately set on fire.

However, the Allahabad High Court reversed the conviction in 2003. It questioned the credibility of the prosecution witnesses, noted inconsistencies in their testimonies, and expressed doubt about the dowry demand itself.

The High Court went so far as to reason that since the accused were poor, they were unlikely to demand expensive items like a television and motorcycle.

It also observed that since there was allegedly no dowry demand before marriage, it was difficult to accept that heavy demands could arise later.

It was this acquittal that the State of Uttar Pradesh challenged before the Supreme Court.

Dowry described as a cross cultural and constitutional evil

Before analysing the evidence, the Supreme Court placed the issue of dowry in a wider social and constitutional frame. In unusually detailed observations, the Court described dowry as a deeply rooted social disease that has transcended religion, region, and class.

The Court stated in clear terms:

“Evil, unless eradicated, can never be contained.”

Tracing the historical evolution of dowry, the judgment noted how a practice originally meant to support women financially had transformed into an institutionalised system tied to status, hypergamy, and social pressure.

The Court observed that dowry has now “divorced itself entirely from the well-being of the female” and has instead become what is referred to as the “groom price theory”.

The judgment makes a strong constitutional link, declaring:

“The eradication of dowry is an urgent constitutional and social necessity.”

It further held that dowry directly violates Article 14 of the Constitution, noting that it undermines equality before the law and treats women as a source of financial extraction rather than equal citizens.

Importantly, the Court rejected the notion that dowry is confined to one community.

While acknowledging that Islamic law mandates mehr as a compulsory gift from the groom to the bride, the Court candidly observed that dowry has entered Muslim marriages in India through cultural assimilation and social emulation.

It noted that in many cases, mehr survives only in nominal form, while real financial transfers flow from the bride’s family to the groom, eroding women’s financial security.

Re examination of evidence and witness testimony

Turning to the facts of the case, the Supreme Court found that the trial court had correctly appreciated the evidence.

The father of the deceased testified that Nasrin had visited her parental home ten to twelve times after marriage and had repeatedly complained of harassment for dowry.

He stated that Ajmal Beg himself reiterated the dowry demand on 4 June 2001, just a day before her death.

The Court noted that this aspect of the prosecution case remained unshaken. It also found that the evidence of the mother and maternal uncle of the deceased consistently pointed to continuous harassment and threats.

While acknowledging inconsistencies in witness statements, the Supreme Court emphasised that criminal trials cannot be derailed by minor contradictions.

Referring to settled law, the Court reiterated that the rule of “falseus in uno falsus in omnibus” does not apply rigidly in Indian criminal jurisprudence.

The Court observed that witnesses recounting traumatic events may falter on details but that this does not destroy the core truth.

It held that the essential facts stood firmly established: there was a demand for dowry, the deceased was harassed for it, the demand was reiterated shortly before her death, and she died an unnatural death within seven years of marriage.

“Soon before her death” explained and applied

A key legal issue was whether the requirement of “soon before her death” under Section 304B IPC was satisfied.

The Supreme Court rejected any narrow interpretation of the phrase.

Relying on earlier judgments, it emphasised that the expression must be understood in the context of human conduct and social realities.

The Court quoted precedent to explain that “soon before her death” is meant to establish a reasonable and proximate link between dowry related cruelty and the death, not an immediate or instantaneous connection.

Applying this principle, the Court found that the facts of the case clearly met the requirement.

The dowry demand was reiterated just one day before Nasrin’s death. The harassment was continuous.

The Court therefore held:

“The presumption under Section 113-B of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 came into effect as soon as it stood proved that the deceased had been subjected to cruelty soon before her death, and went unrebutted by the defence, since no evidence was led by them.”

Strong rejection of High Court reasoning

The Supreme Court was unsparing in its criticism of the reasoning adopted by the Allahabad High Court.

It categorically rejected the logic that poor persons would not demand dowry because they could not afford to maintain the demanded articles, stating plainly:

“This reason does not appeal to reason.”

The Court also rejected the idea that absence of dowry demand before marriage negated later demands.

Referring to the statutory definition of dowry, it clarified that any demand made before, at the time of, or at any time after marriage falls within the scope of the law.

The judgment clearly stated:

“So, the demand by Ajmal and or his family members for a colour TV, a motorcycle and Rs. 15,000/- in cash, unquestionably constitutes dowry.”

The Supreme Court further noted that while reversing the trial court’s findings, the High Court had failed to record any clear reasons demonstrating that those findings were perverse or illegal.

Restoration of conviction and sentencing approach

After analysing the evidence and law, the Supreme Court restored the conviction of both Ajmal Beg and Jamila Beg. Ajmal Beg was directed to surrender within four weeks to serve the sentence awarded by the trial court.

In the case of Jamila Beg, who was recorded to be ninety four years old, the Court took a humanitarian view.

While restoring her conviction, it refrained from sending her to prison, observing that incarceration at such an advanced age could be inhumane and compromise dignity.

Wider observations on dowry deaths and enforcement failures

The judgment also addressed the broader failure of dowry laws to eradicate the practice. Quoting earlier judicial observations, the Court recalled:

“Young women of education, intelligence and character do not set fire to themselves to welcome the embrace of death unless provoked and compelled to that desperate step by the intolerance of their misery.”

The Supreme Court acknowledged that despite decades of legislation, dowry deaths and cruelty cases remain alarmingly high.

It recognised the tension between ineffective enforcement of the law and its misuse in some cases, describing this as a judicial challenge that demands sensitivity rather than denial.

The Court also noted with concern that the present case began in 2001 and could only be concluded in 2025, underscoring the urgent need for faster investigation and trial in dowry related offences.

Throughout the judgment, the Supreme Court repeatedly returned to the human dimension of the crime.

It emphasised that dowry deaths are not abstract statistics but the violent end of young lives shaped by fear, pressure, and relentless cruelty within the supposed safety of marriage.

Case Details

- Case Title: State of Uttar Pradesh vs Ajmal Beg and Another

- Court: Supreme Court of India

- Bench: Justice Sanjay Karol and Justice Nongmeikapam Kotiswar Singh

- Case Type: Criminal Appeals

- Appeal Numbers: Criminal Appeal Nos. 132–133 of 2017

- Originating FIR: FIR No. 94 of 2001

- Police Station: Kiratpur Police Station, District Bijnor, Uttar Pradesh

- Sections Invoked: Section 304B IPC (Dowry Death), Section 498A IPC (Cruelty by Husband or Relatives), Sections 3 and 4 of the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961

- Victim: Nasrin, a woman in her early twenties

- Accused: Ajmal Beg (husband), Jamila Beg (mother-in-law)

Follow The Legal QnA For More Updates…

State of Uttar Pradesh vs Ajmal Beg and Another