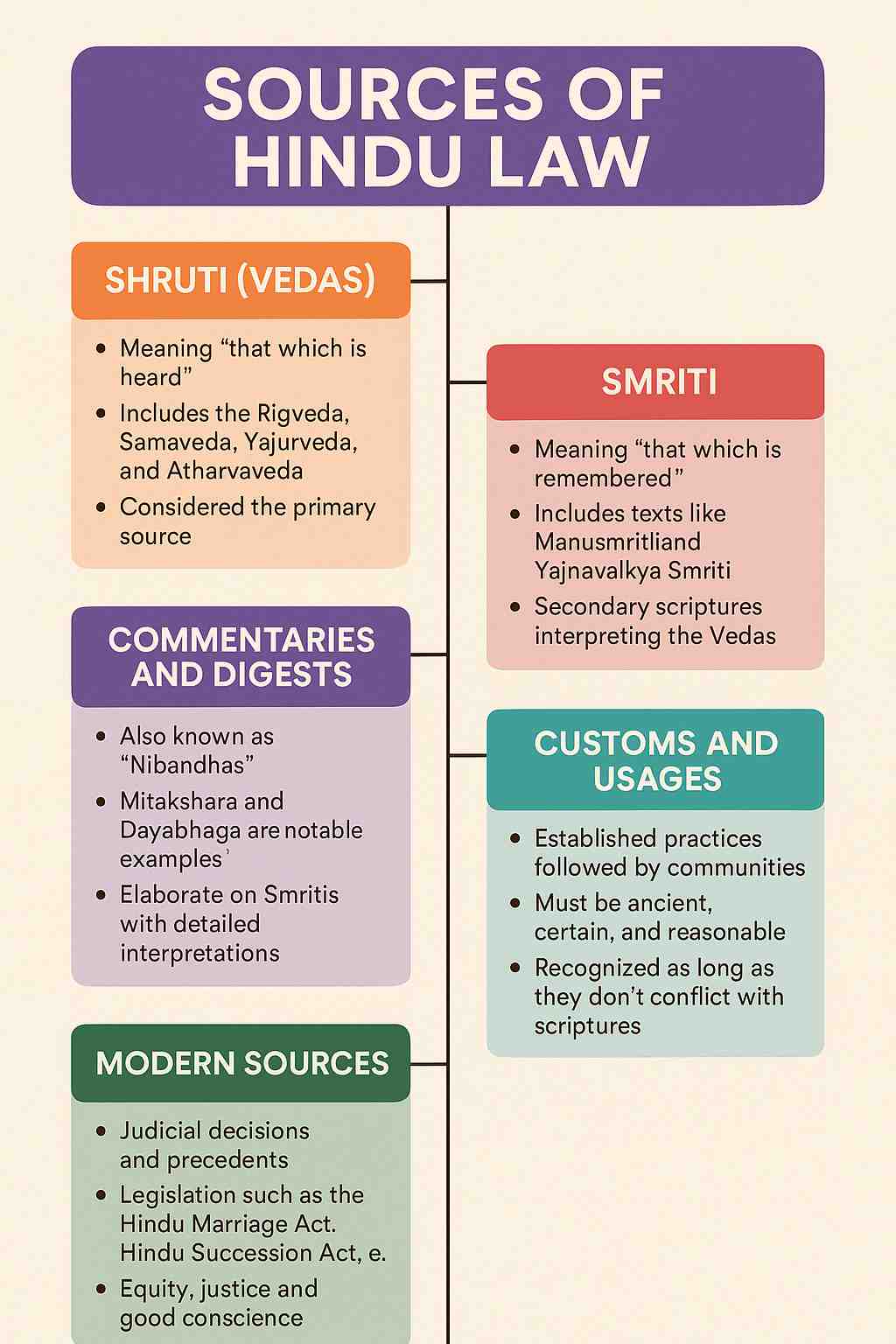

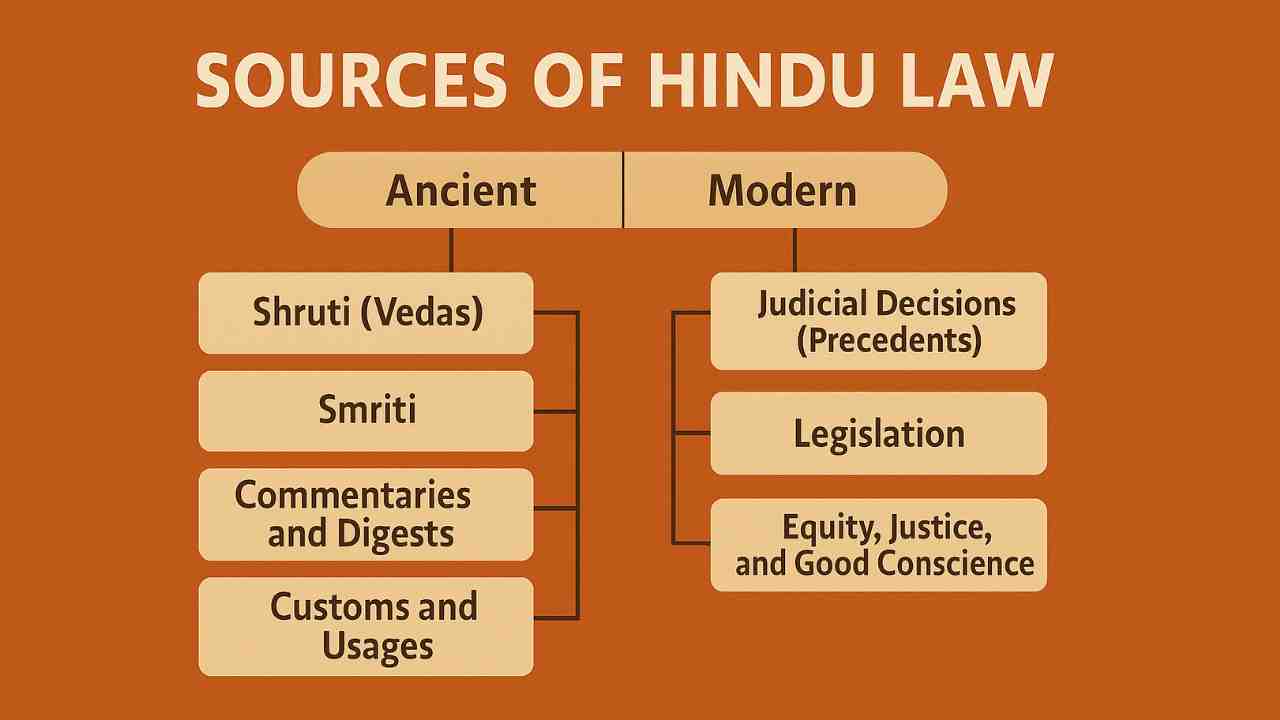

Sources of Hindu law are classified into ancient and modern. Ancient sources include Shruti, Smriti, customs, and commentaries, while modern sources comprise judicial decisions, legislation, and principles of equity, justice, and good conscience. These sources form the foundation of Hindu personal law in India.

Hindu law is one of the oldest legal systems in existence. It governs personal matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, guardianship, and maintenance for individuals who follow Hindu customs. This includes not only those born into the Hindu religion but also anyone who accepts its practices or has been legally recognized as a Hindu under Indian law. The foundations of Hindu law are drawn from religious scriptures, social customs, and legal commentaries that evolved over several centuries.

“Hindu law is not the command of a sovereign, but the rule of conduct founded on customs and religious texts, accepted by the community as binding.”

-P.V. Kane, History of Dharmaśāstra

Historically, this legal system was not based on formal legislation but derived from sacred texts such as the Vedas. Over time, scholars wrote interpretations that helped explain and apply the rules in everyday life. Different regions followed different schools of thought, most notably the Mitakshara and Dayabhaga schools. In modern India, Hindu law operates within a constitutional framework, reinforced by statutes and judicial decisions.

The scope of Hindu law is personal and civil. It does not address criminal matters but focuses on family structure, social duties, and rights within domestic relationships. It remains a key part of India’s legal system and continues to affect a large portion of the population in their everyday lives.

Application of Hindu Law

Origin of the Term “Hindu”

The term Hindu traces its roots to the Old Persian adaptation of the Sanskrit word “Sindhu,” referring to the Indus River. Over time, it came to signify individuals who followed religious traditions rooted in the Indian subcontinent. However, since Hinduism lacks a rigid or universally accepted definition, identifying someone as a Hindu often relies on context and legal interpretation rather than a precise doctrinal test.

Section 2 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

The application of Hindu law is codified in various statutes, notably the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. Section 2 outlines who is governed by Hindu law, primarily through two main criteria:

#1 By Religion

A person is considered Hindu under the law if they profess any of the following religions:

- Hinduism

- Jainism

- Buddhism

- Sikhism

- Inclusion of Hindu Sects: In the landmark case Sastri v. Muldas, the Supreme Court clarified that followers of sects like Swaminarayan, Arya Samaj, and Satsangis are also considered Hindus.

Converts and Reconverts

Even those who were not born Hindu can be governed by Hindu law if:

- They convert to Hinduism, or

- Reconvert after having previously left the faith

In Perumal v. Ponnuswami, the court held that a person becomes Hindu if they demonstrate an intent to adopt the faith and actively engage in its practices.

#2 By Birth

A person is Hindu by birth in the following cases:

- If both parents are Hindu, the child is automatically Hindu

- If one parent is Hindu and the child is raised in a Hindu environment, the child is also considered Hindu under the law

#3 Negative Definition

In legal terms, a person is presumed to be governed by Hindu law if they are not:

- Muslim

- Christian

- Parsi

- Jew

Presumption of Hindu Law

In several cases, Indian courts have ruled that when a person’s religious identity is ambiguous, and they are not governed by any other personal law, Hindu law may automatically apply.

Importance of Sources of Hindu Law

Hindu law is not based on a single book or legislative act. It is a result of various historical and religious sources that have contributed to its development. The earliest sources include the Shruti, which are the four Vedas believed to be divine revelations. These were followed by the Smriti, which are texts written by sages offering rules of conduct and guidelines for moral living. Among these, the Manusmriti and Yajnavalkya Smriti hold particular significance.

“Hindu law is not just law in the modern legal sense, but a code of living that governs moral, ethical, and spiritual behavior.”

-Dr. B.N. Rau, Constitutional Advisor to the Constituent Assembly

In addition to these sacred texts, the opinions of legal scholars through commentaries and digests helped shape Hindu law across regions. Practices followed by different communities, as long as they were reasonable and not immoral, also became recognized as sources of law.

In modern times, Hindu law has been significantly influenced by legislative acts such as the Hindu Marriage Act and Hindu Succession Act. Court decisions have also clarified how these laws should be applied in real-life cases. Together, these sources form a structured system that is both rooted in tradition and open to reform.

Today, Hindu law continues to play a major role in India’s personal law framework. Although the country has adopted many features of a modern legal system, personal matters related to marriage, property, and family are still governed by religious laws for different communities. Hindu law applies to a significant portion of the population and is actively used in family courts and civil procedures.

The legal system continues to rely on ancient principles while applying them to present-day issues. Laws are being reinterpreted to align with contemporary values of equality, individual rights, and social justice. As a result, Hindu law remains an evolving system that reflects both historical depth and modern relevance.

Classification of Sources of Hindu Law

Hindu law, shaped over centuries, draws its legitimacy from two main classifications: ancient sources and modern sources. These two pillars form the basis of personal laws that continue to govern a large section of the Indian population.

Ancient sources refer to the foundational texts and traditions that originated during the Vedic period and evolved through societal practices. The first among them is Shruti, which includes the Vedas. These are considered the earliest expressions of legal and moral conduct. Following this is Smriti, a category comprising texts such as Manusmriti and Yajnavalkya Smriti. These writings provided detailed rules on daily life, duties, marriage, inheritance, and criminal acts. Over time, scholars wrote commentaries and digests to interpret these Smritis. Works like Mitakshara and Dayabhaga became central in shaping regional legal practices. In addition to written texts, customs and usages played a vital role. These were local traditions accepted by communities and recognized as binding if practiced consistently over time.

Modern sources emerged during and after British colonial rule and reflect the shift toward codified legal systems. The most prominent modern source is legislation. Several Acts passed by the Indian Parliament restructured Hindu personal laws, including the Hindu Marriage Act, Hindu Succession Act, and Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act. Another important source is judicial decisions. Indian courts interpret personal laws and set binding precedents through judgments, playing an active role in the development of Hindu law. Lastly, equity, justice, and good conscience serve as a fallback where codified law and precedent are silent. Courts apply these principles to resolve cases fairly when no specific rule is available.

Together, ancient and modern sources have transformed Hindu law into a living system that adapts while retaining its legal and cultural roots.

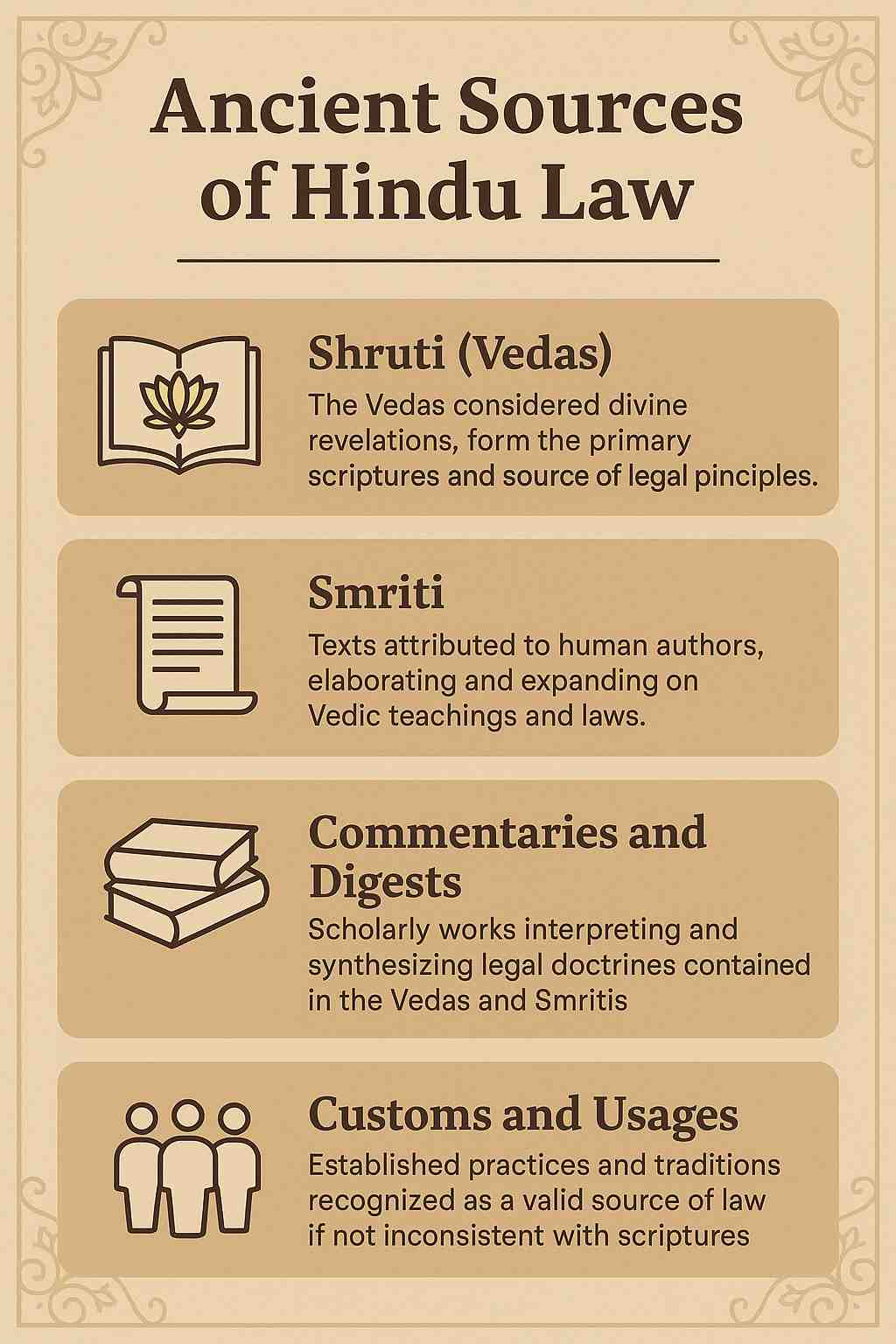

Ancient Sources of Hindu Law

Ancient Hindu law is rooted in a body of texts and traditions that were considered divine and authoritative for centuries. These sources formed the foundational framework that guided every aspect of life, including personal duties, social norms, and legal obligations.

#1 Shruti (Vedas)

Shruti refers to what was “heard” and passed down orally by sages. It represents the earliest and most sacred source of Hindu law. These texts were not authored by any human and are believed to be of divine origin. Shruti laid the foundational rules of dharma, or righteous conduct, which include moral and legal principles.

The teachings in Shruti were meant to guide not just religious life but also the conduct of individuals in society. Though not structured like modern legal codes, the Vedic hymns and verses contain ethical instructions that evolved into legal customs over time.

Components: Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda, Atharvaveda

Shruti is composed of four main Vedas:

- Rigveda contains hymns dedicated to various deities and is considered the oldest and most important.

- Samaveda consists mainly of chants derived from Rigveda, intended for musical recitation during rituals.

- Yajurveda provides the procedural details and formulas used in sacrificial rituals.

- Atharvaveda deals with everyday life and includes spells, charms, and incantations aimed at healing, protection, and social order.

Each of these texts contributed to shaping moral duties and prescribed behaviors, which eventually influenced legal standards.

Role in Formulating Legal Principles

Though the Vedas did not provide direct legal codes, the duties they imposed were eventually interpreted into rules that governed social behavior. The Vedic concept of rita, which signifies cosmic order, later evolved into dharma, the concept central to Hindu law.

Priests and scholars interpreted these divine instructions into practical norms. Over centuries, these interpretations formed the roots of more structured legal texts like the Smritis and later commentaries.

#2 Smriti

Smriti means “that which is remembered.” These texts are human-authored and were written to simplify and systematize the broad and often abstract teachings of Shruti. While Shruti is considered eternal and divine, Smriti is accepted as secondary but more practical in nature.

Smritis include law books, epics, and moral treatises. They were composed by sages who interpreted Vedic teachings for the benefit of society. They provided guidance on duties, law, and governance.

There are three types of Smritis:

- Dharmashastras (law books)

- Itihasas (epics like Mahabharata and Ramayana)

- Puranas (mythological and religious narratives)

Notable Texts: Manusmriti, Yajnavalkya Smriti

Two of the most influential texts are:

- Manusmriti, attributed to sage Manu, is perhaps the most well-known. It elaborates on duties of individuals, legal procedures, punishment for crimes, and roles of rulers.

- Yajnavalkya Smriti is more concise and practical. It includes sections on legal disputes, inheritance, partition of property, and judicial conduct.

These texts deeply influenced not only ancient society but also the colonial codification of Hindu law.

Influence on Hindu Jurisprudence

The Smritis shaped the social and legal framework of ancient Indian communities. Kings and local councils used their principles to resolve disputes and administer justice. Many rules regarding marriage, caste duties, succession, and contracts found in modern Hindu law can be traced back to these texts.

#3 Commentaries and Digests

As Hindu society expanded across different regions, a single uniform application of Smriti-based law became increasingly difficult. Variations in language, cultural practices, and localized traditions led to the emergence of distinct interpretations. Learning scholars began composing detailed explanations of Smriti texts, known as commentaries (tikas) and digests (nibandhas) to address this complexity. These works were pivotal in refining and adapting Hindu law for practical use in different parts of the Indian subcontinent.

Commentaries provided a line-by-line interpretation of earlier Smriti texts, while digests sought to compile and harmonize conflicting rules from various sources. In doing so, these texts did not merely clarify the law but also shaped it by choosing which interpretations to prioritize. Their authority often came to rival that of the original Smriti texts, especially when they resolved contradictions or addressed issues not previously codified.

Mitakshara and Dayabhaga

Among the numerous commentaries and digests written over the centuries, two stand out for their far-reaching impact:

Mitakshara

The Mitakshara, composed by Vijnaneshwara, is a commentary on the Yajnavalkya Smriti. It systematized and interpreted Vedic and Smriti principles, offering a more logical and structured understanding of family and property law. Its influence extends over a vast portion of India, including Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and parts of northern India.

Mitakshara emphasizes joint family ownership and the right by birth in ancestral property. Under this system, male members of a joint family acquire an interest in coparcenary property as soon as they are born.

Dayabhaga

The Dayabhaga, authored by Jimutavahana, is followed primarily in West Bengal and Assam. Unlike Mitakshara, this digest does not treat birth as the basis of property rights. Instead, ownership is established after the death of the father, granting greater control and freedom to the head of the family during his lifetime.

The Dayabhaga school gives relatively more recognition to women’s rights, including provisions for inheritance by widows, which marked a progressive shift from earlier patriarchal norms.

These two texts are not merely academic interpretations; they form the foundation of the two major schools of Hindu law. Their legal theories continue to influence statutory law, judicial reasoning, and family court rulings in India.

Impact on Legal Interpretations

The divergence between Mitakshara and Dayabhaga has profound implications for the legal treatment of property, succession, and family relations. For example:

- Under Mitakshara law, coparcenary property cannot be freely willed away by the father without the consent of other coparceners.

- In contrast, Dayabhaga law allows the father to exercise complete ownership during his lifetime, which includes the right to bequeath his property.

Such distinctions affect judgments in partition suits, succession claims, women’s inheritance rights, and the classification of self-acquired versus ancestral property.

Over time, Indian courts have relied heavily on these commentaries to decide cases where legislative provisions are silent or ambiguous. The flexibility provided by these texts allows judges to adapt traditional Hindu legal norms to modern realities without straying from doctrinal roots.

Even after the codification of Hindu law through statutes like the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, these commentaries continue to be relevant. Courts still refer to Mitakshara and Dayabhaga in cases involving coparcenary property, HUF (Hindu Undivided Family) taxation matters, and interpretations of customary practices.

These texts also reflect the pluralistic nature of Hindu law, where local customs and scholarly interpretations coexist with formal legislation. Their continuing legacy illustrates how ancient legal principles can evolve through interpretation while remaining rooted in tradition.

#4 Customs and Usages

Customs and usages form one of the most practical and living sources of Hindu law. Unlike the sacred texts or commentaries, which often remain confined to religious or academic interpretation, customs reflect the real-life practices of people across generations. These are unwritten rules that have governed conduct in families, castes, tribes, and local communities for centuries.

Customs arise out of repeated social behavior and become binding through consistent adherence. Over time, these practices gain moral and legal authority, especially in regions where religious texts may be silent or ambiguous. Hindu law has long recognized the legal force of such customs, provided they meet certain established standards.

Courts in India, both during colonial rule and in the modern legal system, have given legal recognition to customs in various family, inheritance, and social matters. These practices serve as supplementary sources of law and are considered valid unless they are specifically overridden by statutory provisions or contradict established legal principles.

Definition of Custom By Various Jurists

- Salmond: “Custom is the embodiment of those principles which have commended themselves to the national conscience as principles of justice and public utility.”

- Sir Henry Maine: “Custom is a conception posterior to law and not prior to it. It is something which is to be measured, interpreted and justified by law.”

- John Austin: “Custom is a rule of conduct which the governed observe spontaneously and not in pursuance of law settled by a political superior.”

- Halsbury’s Laws of England: “A custom is a particular rule which has existed from time immemorial and has obtained the force of law in a particular locality, although it is not embodied in legislation.”

- Keeton: “Custom is a rule of conduct, obligatory on those who are within its sphere, established by long usage and consent of the community.”

Section 3(a) of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

Section 3(a) defines the terms “custom” and “usage” as per the codified Hindu law. It recognizes that certain practices followed over time by a community, group, or family can attain the force of law, provided they meet specific legal conditions.

Essentials for a Valid Custom (as per Section 3(a)):

- Continuity: The practice must be ongoing without any significant interruption.

- Uniform Observance: It must be followed consistently by the people concerned.

- Practised for a Long Time: The custom must be ancient, traditionally accepted over many years or generations.

- Certainty: It must be specific and clearly understood, not vague or unclear.

- Reasonableness: The custom should not be irrational, oppressive, or arbitrary.

- Not Opposed to Public Policy: Customs that contradict public morals, statutory law, or fundamental rights will not be upheld.

- Not Discontinued by the Family (in Family Customs): If the custom applies to a family, it must not have been abandoned at any point in time.

If all the above requirements are met, the custom becomes legally enforceable within the group, locality, or family where it is practiced.

Deivanai Achi vs. Chidambaram Chettiar (1953)

The Madras High Court held that for a custom to be legally valid, it must be:

- Continuously practiced by the people.

- Clear and not ambiguous.

- Not against public policy.

Laxmibai vs. Bhagwanthbuva (2013)

The Supreme Court of India ruled that for a custom to gain legal enforceability, it must be:

- Continuously practiced.

- Accepted by the majority within the group or community.

Legal Status of Customs in Hindu Law

In the absence of applicable rules from Shruti, Smriti, or judicial precedents, courts have often resorted to customary law to resolve disputes. Hindu law does not treat customs as inferior; rather, it grants them the authority of law if they fulfill certain legal conditions. These conditions ensure that not every social habit is given legal sanction but only those that have been time-tested, accepted by the community, and meet standards of fairness.

For instance, if a particular community has followed a property inheritance pattern through the maternal line for generations, and this practice is known, followed, and accepted by all members, courts may uphold such a custom even if classical texts remain silent on the subject.

Criteria for Valid Customs

Not all customs are considered legally binding. Hindu law, supported by judicial interpretation, outlines specific criteria that a custom must satisfy to attain the status of law:

- Antiquity: The custom must be ancient. Courts generally expect the practice to have been in existence for a considerable duration, often going back several generations.

- Continuity: The practice must be continuous. If it has been abandoned or broken for a significant time, it may lose its legal validity.

- Certainty: The custom must be specific and clearly defined. A vague or loosely followed habit cannot be enforced by law.

- Reasonableness: The custom must not be irrational or oppressive. It should not violate principles of natural justice or fairness.

- Not Opposed to Public Policy: Customs that conflict with public morality, basic human rights, or statutory law are not recognized.

- Accepted as Binding: The community must regard the custom as legally obligatory, not merely a social preference or convenience.

Types of Customs under Hindu Law

1. Local Customs

Local customs are practices followed by the people of a specific region, town, village, or district. These customs arise from consistent and long-standing usage unique to a particular locality and are recognized by the courts when they meet the legal criteria for validity. Even if such customs differ from general Hindu law, they are upheld as legally binding within that geographic area, provided they are not opposed to public policy or statutory law.

For example, a village in northern India may follow a unique land inheritance system that passes property to the eldest daughter, which, although not part of the classical Hindu texts, could be enforced if the practice is ancient, certain, and accepted by the community.

2. Class or Caste Customs

These customs are observed by specific social groups such as castes, sub-castes, sects, or communities within the Hindu society. They are binding only on the members of that group and have evolved to address the cultural and practical needs of those specific communities. Class or caste customs often regulate marriage rules, dietary practices, rituals, and inheritance.

For instance, while general Hindu law may prohibit marriage between certain relatives, some communities, such as the Tamil Vellalars, traditionally permit cross-cousin marriages. Courts recognize such caste-specific customs if they fulfill the requirements of antiquity, certainty, and general acceptance within that group.

3. Family Customs

Family customs are long-standing practices followed by a particular family over generations. These customs may relate to matters such as succession, property division, marriage traditions, or religious rituals, and are binding only within that family. For a family custom to be recognized legally, it must be ancient, certain, uniformly followed, and accepted as obligatory by all family members. Importantly, such customs must not violate public policy or contradict statutory provisions.

For example, a family may have a tradition of appointing the eldest female as the sole manager of ancestral property. If this has been consistently and voluntarily followed for a long time, the court may recognize it as a valid family custom.

4. General Customs

General customs are those practices which are widely observed by the entire Hindu community or a substantial portion of it, across regions and castes. These customs form the foundation of Hindu law itself and are presumed to be universally binding unless there is evidence to the contrary. General customs have been absorbed into legal texts and judicial interpretations over time.

An example includes the recognition of the vivaha (marriage) as a sacramental union under Hindu law, which originates not from a statute but from a universally accepted custom across Hindu society. Unlike local or caste customs, general customs have a broader and more authoritative scope.

Examples in Practice:

Customs have influenced several areas of personal law. Some prominent examples include:

- Marriage rituals and eligibility: In certain communities, specific forms of marriage, such as Swayamvara or regional ceremonial customs, are still recognized due to their long-standing tradition.

- Property and inheritance rights: Some tribal or matrilineal societies in regions like Kerala and the North-East have unique rules regarding inheritance through female lineage, which have been legally upheld based on customary practice.

- Guardianship and family roles: In some rural areas, decisions about child guardianship are governed not just by statutory law but by customary practices that are respected by the community.

- Ceremonial observances: Funeral rites, name-giving traditions, and other lifecycle events often follow community-specific customs that have the force of law in personal matters.

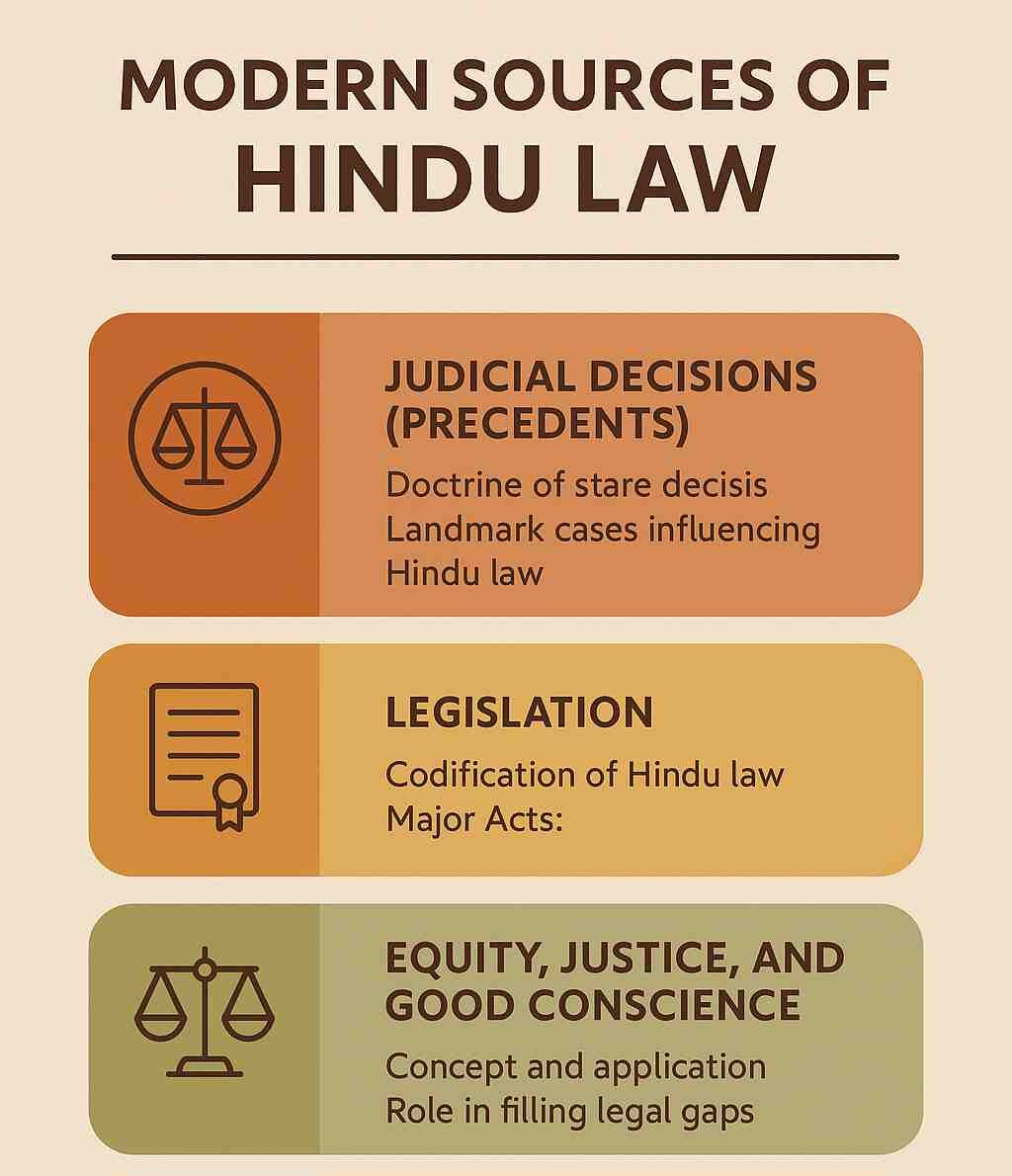

Modern Sources of Hindu Law

Modern sources of Hindu law are those that have developed through statutory interventions, court rulings, and principles applied by judges during the British and post-independence periods. These sources play a crucial role in shaping how Hindu personal laws operate in contemporary India.

#1 Judicial Decisions (Precedents)

Doctrine of Stare Decisis: Stare decisis is a foundational legal principle that obligates courts to follow previous rulings in similar cases. When a higher court delivers a judgment, that ruling sets a legal standard for lower courts to follow. This ensures consistency and predictability in how laws are applied across different regions and courts.

In Hindu law, judicial precedents have gradually evolved into a binding source of law. Courts interpret religious texts, personal laws, and statutory provisions to resolve disputes. These interpretations, once delivered by higher courts such as High Courts or the Supreme Court of India, are treated as valid legal rules in subsequent cases.

Judicial decisions have filled several gaps in the traditional texts, especially in areas where the scriptures offer no clear guidance, or where their interpretation conflicts with modern legal norms and constitutional principles.

Landmark Cases That Influenced Hindu Law

- Shah Bano Case (Mohd. Ahmed Khan v. Shah Bano Begum, 1985): Although primarily dealing with Muslim law, the case had a major ripple effect across all personal laws, including Hindu law. It led to intense national debate on reforming personal laws and the rights of women after divorce.

- Githa Hariharan v. Reserve Bank of India (1999): This case reinterpreted the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956. The Supreme Court held that both mother and father are natural guardians, providing equal legal recognition to mothers as guardians of minor children.

- Danamma v. Amar (2018): This judgment reaffirmed the right of Hindu daughters to coparcenary property under the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005. The court held that daughters have the same rights as sons, regardless of whether the father was alive when the amendment came into force.

- Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma (2020): The Supreme Court clarified that a daughter has an equal right to ancestral property by birth and is a coparcener, even if her father passed away before 2005. This removed ambiguity left by earlier rulings.

These rulings transformed several aspects of Hindu personal law, including property rights, guardianship, and family obligations. They show how judicial reasoning becomes an active source of law in a modern legal system.

#2 Legislation

Codification of Hindu Law: Before independence, Hindu personal laws were governed primarily by ancient texts and customs. After independence, the Indian government undertook a major reform to bring clarity and uniformity to Hindu law. This process resulted in the codification of major aspects of personal law into specific statutes.

Statutes Governing Hindu Law

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955: This Act regulates all aspects of marriage among Hindus, including conditions for a valid marriage, divorce, judicial separation, restitution of conjugal rights, and nullity of marriage. It introduced monogamy, defined legal age for marriage, and recognized grounds for divorce for both spouses.

- Hindu Succession Act, 1956: This Act governs the inheritance and succession of property among Hindus. It lays out a uniform and systematic framework for the distribution of property among male and female heirs. A landmark amendment in 2005 gave daughters equal rights in coparcenary property.

- Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956: This law outlines the legal process of adoption and the responsibilities of maintaining dependents. It defines who can adopt, who can be adopted, and the rights and obligations that follow adoption. It also places legal duties on individuals to maintain dependents such as wife, children, and aged parents.

- Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956: This Act identifies the legal guardians of Hindu minors and their powers and responsibilities. It clarifies who may act as guardian of the person and property of a minor and places restrictions to prevent misuse of authority.

These four Acts form the statutory foundation of modern Hindu law. They collectively address marriage, inheritance, adoption, guardianship, and family maintenance, replacing the previously scattered and interpretative system based on ancient texts and regional customs.

#3 Equity, Justice, and Good Conscience

In cases where neither legislation nor judicial precedent provides a solution, courts apply principles of equity, justice, and good conscience. These are unwritten principles used by judges to deliver fair and impartial decisions, especially in personal law matters where scriptures or statutes remain silent or unclear.

The application of these principles began during the British era when judges trained in common law were faced with gaps in Hindu law. They resolved cases by applying ethical and rational reasoning instead of rigidly following ancient texts. This approach has been retained in independent India.

For example, courts have invoked these principles in:

- Guardianship cases where the welfare of the child outweighs technical rights.

- Inheritance disputes involving adopted or illegitimate children.

- Maintenance claims where moral obligations take precedence over strict legal definitions.

These values act as a moral compass for judges, ensuring that justice is not denied due to the absence of written law. Their use allows Hindu law to remain flexible and responsive to changing social realities.

Ancient vs. Modern Sources

Hindu law has come a long way over the centuries. In the earliest periods, it was shaped by religious texts such as the Vedas and Smritis. These writings were not just about spirituality or worship. They provided detailed rules about daily life, social roles, family responsibilities, and ethical behavior. Marriage, inheritance, and property rights were all governed through these ancient texts.

The British administration introduced formal legal institutions, written statutes, and a more uniform legal process. Courtrooms replaced councils of priests, and judges began interpreting personal laws using a combination of traditional sources and legal reasoning. This created a significant turning point, as Hindu law started adapting to a legal framework based on fairness, consistency, and written legislation.

Today’s Hindu law is the product of that evolution. It still holds elements from its ancient origins, but it is now closely aligned with the modern legal system in India. This journey reflects how a tradition-based system can grow into a structured and codified form of law that serves the needs of today’s society.

Continuity in Legal Principles

Many principles from the ancient system continue to shape Hindu law even now. For example, the concept of duty within a family, or what is often referred to as dharma, still plays a key role in legal discussions on marriage, care of parents, or inheritance.

At the same time, the way these principles are applied has changed a great deal. In ancient times, laws were often influenced by caste, gender, and religious status. These factors decided who had the right to inherit property, adopt a child, or act as a guardian. In contrast, modern law focuses on equality and fairness. A good example is the change brought by the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005, which gave daughters equal rights in ancestral property. This was a major step away from the older system, which was more restrictive for women.

So while the foundation remains connected to the past, the structure has been rebuilt to reflect the present. Hindu law still honors certain traditions, but the rules now support individual rights and social progress.

Integration of Traditional and Contemporary Norms

One of the most unique aspects of Hindu law today is how it brings together older values and modern legal ideas. Courts still refer to ancient commentaries like Mitakshara and Dayabhaga in some cases. At the same time, they also rely on the Constitution, Acts of Parliament, and judicial precedents.

This blend is visible in every part of personal law. Marriage is one example. Culturally, it is still seen by many as a sacred bond, but legally, it must follow the provisions of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. The same goes for issues like adoption, guardianship, and divorce, which are now guided by well-defined legal procedures but still reflect traditional values in many families.

This dual approach helps Hindu law remain both rooted and relevant. It respects long-held beliefs while making sure that individuals have clear legal protections. By balancing tradition with reform, Hindu law has managed to stay meaningful in modern times without losing touch with where it came from.

Influence of British Colonial Rule on Hindu Law

When the British East India Company took administrative control over Indian territories, it brought with it the legal philosophy and judicial procedures of English common law. Courts established under British rule began applying these principles to adjudicate civil and criminal matters.

However, they faced a unique challenge in matters of personal law, where religious customs governed inheritance, marriage, and family relations. To address this, British judges relied on local customs and religious texts, but interpreted them using English legal reasoning. This practice created a blend of indigenous doctrines and imported legal structures, leading to a shift in how Hindu law was applied in the courts.

Establishment of Anglo-Hindu Law

The British approach to governing personal laws led to the creation of what came to be known as Anglo-Hindu law. This system was not a direct continuation of traditional Hindu jurisprudence, nor was it entirely based on British legal doctrines. Instead, it was a hybrid framework constructed through judicial interpretations of religious scriptures, supported by opinions from court pandits and legal scholars.

Over time, key Hindu texts were translated and codified selectively, often removing flexibility that had previously allowed for regional or community-based variations. The result was a rigid and formal body of rules that often diverged from the practices followed in Hindu society before colonial rule.

The colonial restructuring of Hindu law significantly altered its character. Before British rule, Hindu law was primarily administered through community councils, local jurists, and family elders. It was adaptive, interpretive, and deeply rooted in customs passed down through generations.

British legal institutions, however, introduced codification and uniform procedures that emphasized legal certainty and precedent over customary variation. This shift displaced traditional mechanisms of dispute resolution and centralized authority in colonial courts. Many nuanced practices lost recognition, and the evolving nature of Hindu legal thought was frozen into fixed doctrines.

In addition, the selective recognition of certain texts and commentaries created imbalances. For example, the preference for Mitakshara or Dayabhaga principles in certain provinces ignored localized traditions. These changes not only redefined Hindu law as it was known within communities but also laid the groundwork for modern legislative interventions in post-independence India.

Role of Schools of Hindu Law

Mitakshara School

The Mitakshara School is one of the two principal schools of Hindu law that evolved from ancient commentaries. It is based on the Mitakshara, a legal treatise written by Vijnaneshwara, which is a commentary on the Yajnavalkya Smriti. This school is prevalent across most of India except for Bengal and Assam.

Mitakshara law emphasizes the concept of joint family property. According to this doctrine, a male member acquires a right in ancestral property by birth. This co-ownership begins from the moment of birth, allowing coparceners to demand partition at any time. The father acts as the head of the family (Karta) and manages the property, but does not hold exclusive rights over it.

Inheritance under the Mitakshara School follows the principle of survivorship among male coparceners. Female members were historically excluded from inheritance in ancestral property, though recent statutory amendments have rectified this exclusion.

The Mitakshara system recognizes four sub-schools:

- Benaras School

- Mithila School

- Bombay School

- Dravida or Madras School

Each sub-school has minor regional variations in interpretation but adheres to the core principles laid down in Mitakshara.

Dayabhaga School

The Dayabhaga School, developed by Jimutavahana through his commentary titled “Dayabhaga,” is mainly followed in West Bengal and Assam. This school offers a more progressive view compared to Mitakshara, particularly in matters related to inheritance and individual rights.

Unlike the Mitakshara School, rights in ancestral property do not accrue by birth. A male heir obtains ownership only after the death of the father, making inheritance a posthumous event. Therefore, the concept of coparcenary does not apply in the same way as it does under Mitakshara.

Another key feature of the Dayabhaga School is the greater recognition of women’s rights. Widows, for instance, were entitled to inherit property in the absence of male heirs, a practice not originally supported under the Mitakshara system.

Dayabhaga emphasizes religious efficacy over blood proximity in determining succession. The person most capable of performing the last rites of the deceased is given preference, reinforcing the spiritual aspect of inheritance laws.

Differences in Interpretation and Application

| Feature | Mitakshara School | Dayabhaga School |

|---|---|---|

| Right to Property | Acquired by birth | Acquired after death |

| Coparcenary | Starts at birth among male members | No automatic coparcenary |

| Women’s Rights | Limited under traditional rules | Greater recognition, including the widow’s right to inherit |

| Scope | Pan-India, except Bengal and Assam | Restricted to Bengal and Assam |

| Basis of Inheritance | Survivorship principle | Religious efficacy principle |

The practical applications of these differences affect several areas, including property partition, rights of female heirs, and legal challenges in succession disputes. Courts continue to interpret these provisions with evolving social standards and statutory amendments, such as the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005, which grants daughters equal coparcenary rights.

Application of Hindu Law in Contemporary India

In present-day India, Hindu law governs a wide range of civil matters for individuals who identify as Hindus, including Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs. It applies in areas such as marriage, divorce, adoption, guardianship, and succession. The legal framework is primarily based on codified laws passed by the Indian Parliament and is enforced through both civil courts and family courts.

The key statutes include:

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

- Hindu Succession Act, 1956

- Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956

- Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956

These legislations have codified and reformed many traditional practices. Courts now have wider discretion to ensure justice, especially in cases involving gender rights, child custody, and matrimonial disputes.

Uniform Civil Code Debate

The Uniform Civil Code (UCC) remains a subject of ongoing political and legal discussion in India. The idea behind the UCC is to have a common set of personal laws governing all citizens regardless of religion. Supporters argue that it promotes equality and national integration, while critics fear it could override religious customs and minority rights.

Hindu law often finds itself at the center of this debate due to its widespread application and complex mix of religious and secular elements. Reforms within Hindu personal law are sometimes cited as examples of modernizing religious codes, which proponents of UCC suggest should be extended to all communities. However, opponents emphasize that imposing a uniform system may violate cultural autonomy and religious freedom.

The discussion around UCC illustrates the friction between tradition and modern constitutional values, particularly the principle of equality before the law.

Judicial Trends and Reforms

Indian judiciary has played a key role in shaping the direction of Hindu law in recent decades. Several landmark judgments have redefined traditional concepts and expanded the scope of statutory interpretation. Courts have proactively interpreted codified laws in light of the Indian Constitution, especially concerning gender justice and social equity.

Notable judicial interventions include:

- Granting equal coparcenary rights to daughters in ancestral property (Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma, 2020)

- Recognizing live-in relationships under certain conditions for protection under domestic violence laws

- Ensuring maintenance rights for divorced Hindu women

Courts have consistently leaned toward progressive interpretations to align personal laws with evolving societal values. This judicial trend shows that Hindu law is not static but continually shaped by constitutional principles and changing social expectations.

Verdict

Hindu law combines ancient texts, customs, and modern legislation to govern personal matters like marriage, inheritance, and adoption. The Mitakshara and Dayabhaga schools shape regional interpretations, while legal reforms and court rulings continue to modernize its application, making Hindu law both adaptable and legally relevant in today’s India.

The legal structure of Hindu law represents a unique fusion of tradition and reform. Rooted in ancient scriptures like the Shruti and Smriti, and further developed through authoritative commentaries and customs, Hindu law was later shaped by judicial decisions and statutory codification during and after British rule.

The two principal schools, Mitakshara and Dayabhaga, exemplify the diversity within Hindu jurisprudence. While Mitakshara grants coparcenary rights by birth and dominates most regions of India, Dayabhaga follows a succession-based system with a stronger emphasis on individual ownership and wider inclusion of female heirs.

Modern Hindu law is primarily governed by legislative acts introduced in the mid-20th century. These laws have been instrumental in addressing gender inequalities, ensuring legal clarity, and introducing uniformity where feasible. Judicial interventions have further strengthened these reforms by aligning interpretations with constitutional values like equality, justice, and non-discrimination.

Today, Hindu law functions as both a traditional and evolving legal system. It accommodates cultural heritage while addressing contemporary social issues. As debates around the Uniform Civil Code and gender justice continue, Hindu law remains a critical area of personal law in India, reflecting both legal continuity and responsive change.

Follow The Legal QnA For More Updates…