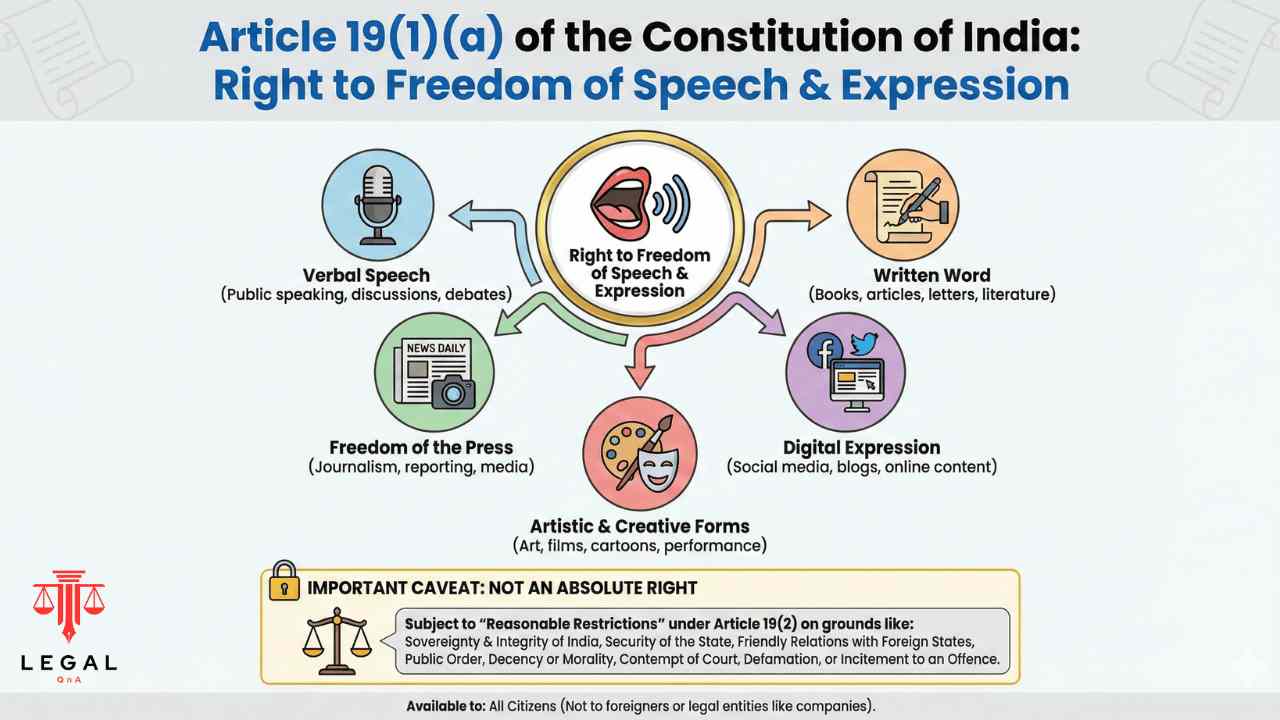

- Guarantees Free Speech: Article 19(1)(a) secures the fundamental right for all Indian citizens to express their views, opinions, and convictions freely by word of mouth, writing, printing, or picturization.

- Protects Freedom of the Press: While not explicitly mentioned in the text, the Supreme Court has consistently ruled that the “freedom of the press” is an integral part of this article.

- Includes the Right to Know: This article is the constitutional basis for the Right to Information (RTI), affirming that citizens have a right to be informed about government activities.

- Right to Silence: The judiciary has interpreted the freedom of expression to also include the “negative right” to remain silent, such as not being forced to sing.

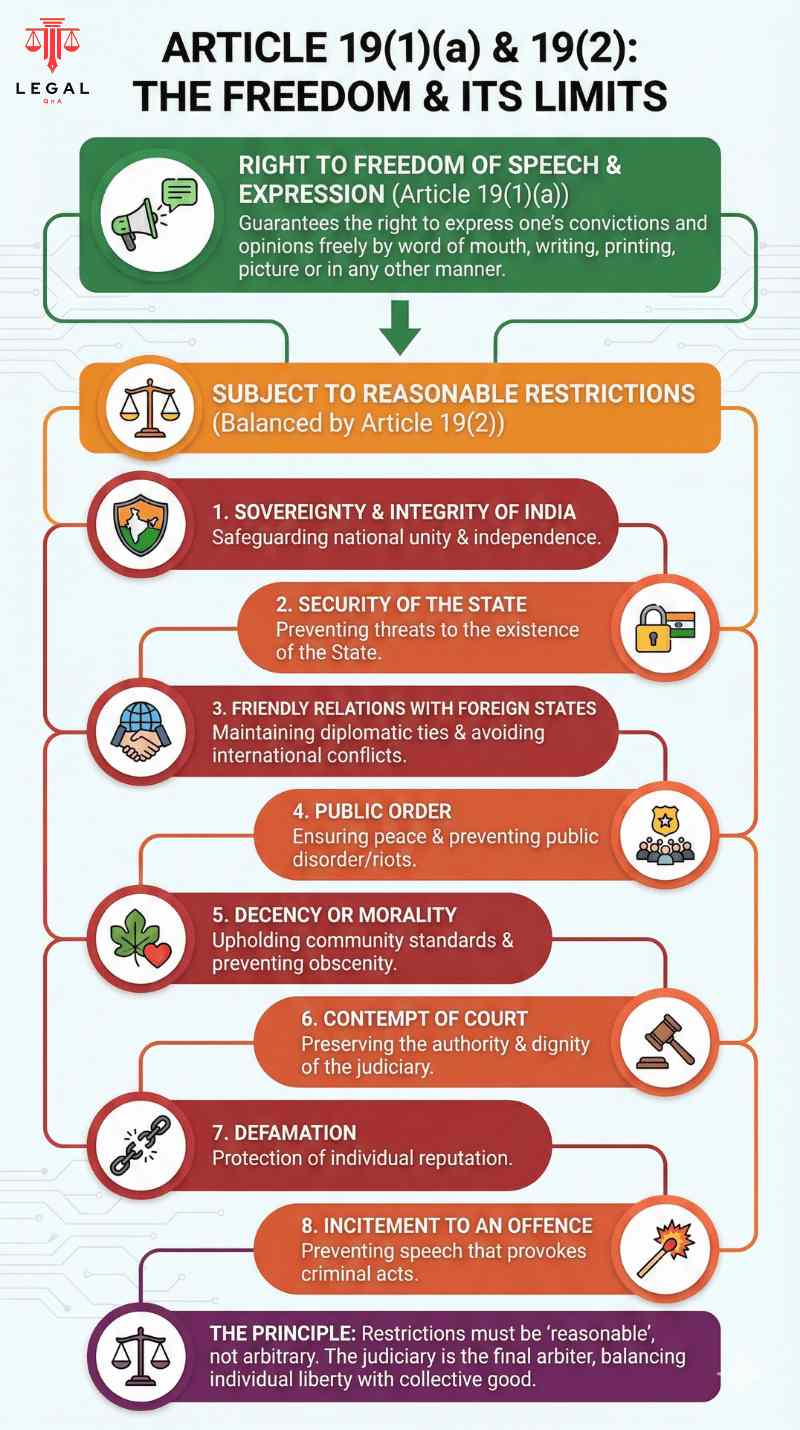

- Not an Absolute Right: This freedom is not uncontrolled; the State can impose “reasonable restrictions” under Article 19(2) for reasons like sovereignty, public order, decency, or defamation.

Freedom of speech and expression is not merely a constitutional clause but the oxygen that sustains every democratic pulse of this nation.

Without it, Parliament becomes an echo chamber, journalism transforms into state-sponsored recital, and citizens are reduced to obedient spectators rather than active participants in governance.

When the framers incorporated Article 19(1)(a) into the Constitution of India, they did not carve decorative symbolism; they placed a living, functioning nerve that runs through every democratic institution, every public office, and every citizen’s conscience.

They understood from lived experience that speech, when strangled, does not vanish; it festers, rebels, and eventually erupts.

Colonial rule had taught India that suppression of expression is not merely a legal inconvenience but a political weapon.

The sedition trials of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the censorship of nationalist newspapers, the prosecution of Mahatma Gandhi for advocating civil disobedience, and the constant police watch over editorial rooms were not forgotten at the drafting table.

The framers were not writing in idealistic isolation; they were drafting with ink stained by decades of repression.2q

Article 19(1)(a) succinctly states:

“All citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression.”

A sentence so brief, yet powerful enough to challenge empires, governments, majoritarian sentiments, and the occasional oversensitive authority that confuses criticism with conspiracy.

This provision carries within it the historical memory of every banned pamphlet, every censored speech, every lathi-charge on demonstrators who dared to raise their voice against imperial command.

In a functioning constitutional democracy, speech is not a cultural accessory but a mandatory operational tool.

A nation can survive slow economy, unstable coalition politics, or even monsoon disappointment, but it cannot survive without informed dialogue.

That is precisely why Article 19(1)(a) stands at the constitutional forefront.

It guarantees that every citizen possesses the unqualified right to speak, write, publish, critique, question, argue, satirize, lampoon, and even uncomfortably dissent, without the looming fear of punitive retaliation.

Public discourse is not a luxury reserved for scholarly journals and televised debates; it is the engine of participatory governance.

A Constitution can design institutions, but only free expression animates them. A vote elects a representative, but speech evaluates performance.

A newspaper reports facts, but expression allows accountability. A politician campaigns on promises, but public commentary determines whether such promises survive beyond slogans.

Thus, Article 19(1)(a) is not granted for the comfort of the governing class; it exists for the protection of the governed.

Its objective is not to produce polite agreement but to cultivate informed disagreement. Democracy, after all, is not built on uniform nods but on spirited contestation of ideas.

When citizens speak freely, governance listens honestly. When speech is throttled, governance becomes arrogant, insulated, and dangerously unchecked.

Historical Roots of Article 19(1)(a)

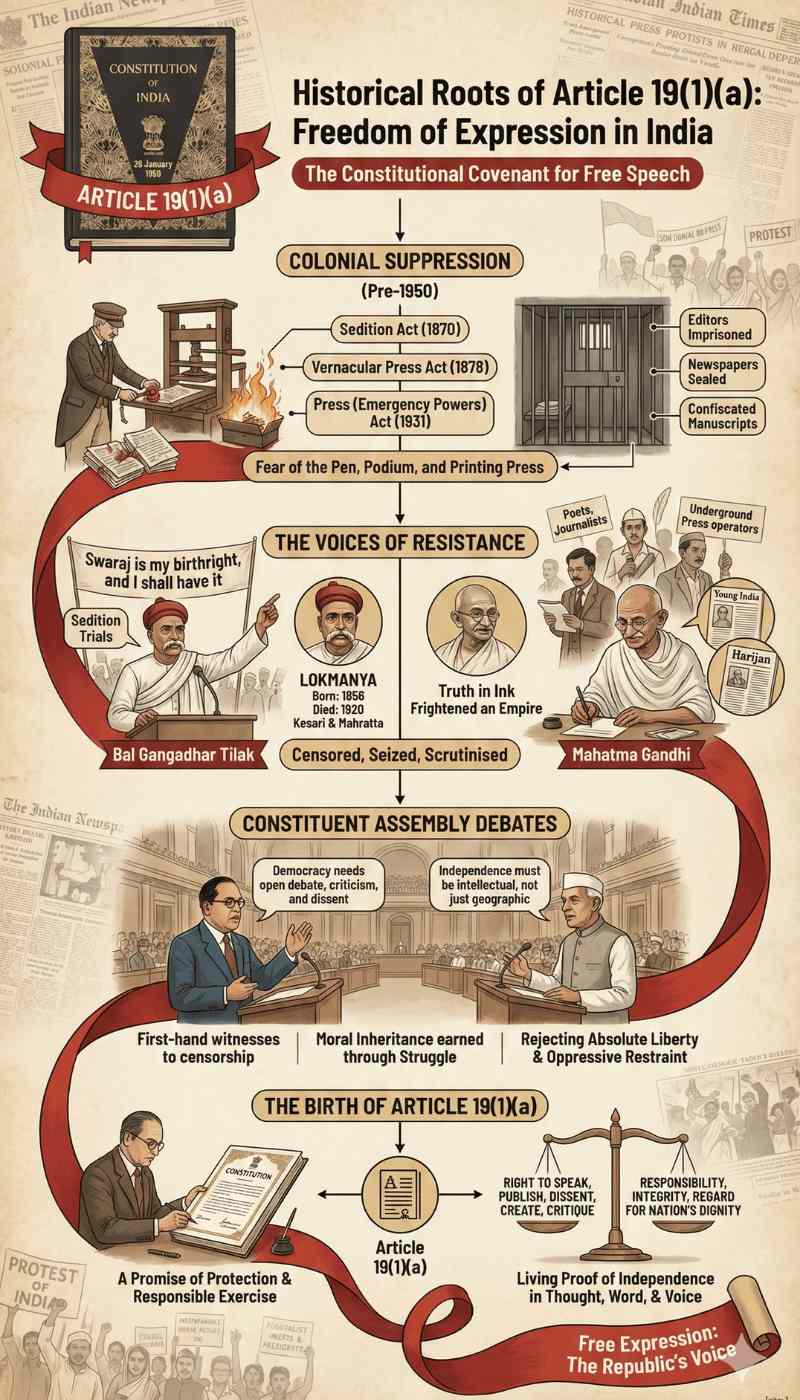

Freedom of expression in India did not suddenly appear on 26 January 1950 with the commencement of the Constitution.

It was cultivated through decades of struggle, courtroom trials, prison writings, underground nationalist presses, and the fiery awakening of a colonised civilisation refusing to remain silent.

Before Article 19(1)(a) took birth in the constitutional text, it lived in the speeches of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who famously declared that “Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it” and paid for it through sedition trials intended to crush his voice rather than contest his ideas.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak

LOKMANYA

- Born: July 23, 1856 (Ratnagiri)

- Died: August 1, 1920 (Mumbai)

- Known for: Indian Independence Movement

- Major Works: Gita Rahasya, The Arctic Home in the Vedas

“Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it.”

It existed in the quiet strength of Mahatma Gandhi’s journals: Young India and Harijan, which were repeatedly censored, seized, and scrutinised because truth written in ink frightened an empire more than armed rebellion.

British rule understood the power of speech far better than many modern regimes are willing to admit.

That is precisely why they enacted a network of legislative chains: the Sedition Act of 1870, the Vernacular Press Act of 1878, the Press (Emergency Powers) Act of 1931, and several executive circulars aimed at preventing Indians from thinking out loud.

Newspapers were sealed, editors imprisoned, manuscripts confiscated, and poems treated as threats. It was not the sword that terrified the colonial state; it was the pen, the podium, and the printing press.

When independent India’s Constituent Assembly finally gathered, the members were not theorising freedom in a textbook sense.

They were first-hand witnesses to punitive censorship, banned publications, and courtroom prejudice. For them, freedom of expression was not a borrowed Western ideal but a moral inheritance earned through blood, satire, journalism, and agitation.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, with his constitutional clarity, insisted that democracy cannot be a mere institutional structure; it must be animated by open debate, criticism, and dissent. A Parliament sealed against opinion becomes a fortress, not a representative body.

Jawaharlal Nehru, having himself faced colonial prosecution for political writings, stood in defence of free expression not as a theoretician but as a survivor of suppression.

He understood that if the government of independent India employed the same speech controls as the colonisers, then independence would be geographic but not intellectual.

The debates in the Assembly make one thing crystal clear: speech must be free, expressive, and fearless, but it must not be reckless or destructive to national security.

They rejected absolute liberty on one hand and rejected oppressive restraint on the other, crafting instead a middle constitutional path through Article 19(1)(a) and the calibrated limitations of Article 19(2).

Thus, Article 19(1)(a) emerged as a solemn constitutional covenant, a promise that the State will protect the citizen’s right to speak, publish, question, dissent, create, and critique.

In return, the citizen shall exercise that right with responsibility, integrity, and regard for the nation’s collective dignity.

Free expression, therefore, is not a mere privilege but the living proof that independence did not end at midnight on 15 August 1947, it continued into the dawn of thought, word, and voice.

Scope and Breadth of Article 19(1)(a)

The Ever-Expanding Constitutional Space of Expression

Article 19(1)(a) is distinguished by its remarkable adaptability. It does not bind expression to any single instrument of communication.

It has travelled comfortably from parchment to printing press, from radio broadcast to global digital conversation, and from traditional reportage to satirical short videos that circulate faster than the morning newspaper.

The Constitution does not merely protect the spoken or written word; it protects communication in every recognisable form.

When the framers drafted the provision, they could not have predicted livestreamed political debates, online activism, encrypted whistleblower documents, or citizen-journalist footage that mobilises public action in minutes.

Yet they were wise enough to understand that liberty must be principle-driven rather than medium-dependent.

Press and Print as the Informational Foundation

The printed word continues to influence public opinion and political integrity. Newspapers and periodicals serve as watchdogs of the administration.

Investigative journalism uncovers scandals that would otherwise remain buried under official files, bureaucratic opacity, and political convenience.

Bennett Coleman & Co. v. Union of India (1973)

In this transformative judgment, the Supreme Court struck down government regulations that restricted the quantity of newsprint available to newspapers. The Court held that limiting newsprint indirectly limits ideas, viewpoints, and circulation, thereby violating Article 19(1)(a). The ruling clarified that press freedom is not merely a right of publishers but a right of citizens to receive information. By protecting editorial independence from economic strangulation, the decision established that the State cannot shrink public discourse by controlling the material through which it flows.

Editorial commentary shapes public understanding and pushes governments toward accountability.

It has been humorously remarked among legal thinkers that if the press ever loses its voice, the State would have a monopoly over public narrative.

Democracy cannot function on selective disclosure. A free press ensures that governance remains visible, debatable, and answerable.

Cinema and Theatre as Creative Expression

Films and theatre productions have historically acted as mirrors of societal truth. They do not merely entertain; they provoke thought, disturb comfort zones, and challenge ideology.

A society that censors artistic discomfort risks becoming intellectually rigid. The Supreme Court has clarified that creative expression cannot be curtailed simply because a section of viewers finds a portrayal inconvenient or ideologically unwelcome.

Artistic expression often questions what ordinary discourse hesitates to articulate.

The stage and the screen give voice to political satire, historical reinterpretation, human suffering, institutional excess, and cultural hypocrisy.

These forms of expression deserve protection not because they are harmless, but because they are honest.

Expression Through Conduct and Silence

Communication is not always verbal. The law recognises symbolic gestures as legitimate forms of expression.

A silent march against custodial brutality, a candlelight gathering for peace, a hunger protest challenging unethical policy, or the deliberate refusal to participate in an act that violates personal conscience are all protected expressions under Article 19(1)(a).

In the well-known Bijoe Emmanuel ruling, the Supreme Court acknowledged that silence can be as communicative as speech.

Bijoe Emmanuel v. State of Kerala (1986)

The Supreme Court upheld the right of three students who stood silently during the national anthem because their religious doctrine prohibited singing. They showed no disrespect, created no disturbance, and maintained dignity throughout. The Court held that compelling them to sing violated freedom of speech under Article 19(1)(a) and freedom of conscience under Article 25. This ruling clarified that respect for the nation is not measured by compulsory vocal participation but by sincere, peaceful conduct.

The students who declined to sing the national anthem did not offend the nation; they asserted religious integrity. The Court correctly observed that the Constitution protects belief as sincerely as it protects speech.

Expression, therefore, includes speech, writing, posture, silence, resistance, and symbolic participation. The law listens not only to spoken words but also to their absence.

Commercial Expression and Public Knowledge

In Tata Press Ltd. v. MTNL, the Court extended constitutional protection to commercial advertising, recognising that consumers require information to exercise economic choice.

Advertising is not merely marketing material; it is a channel through which public awareness is built.

Tata Press Ltd. v. MTNL (1995)

In this landmark ruling, the Supreme Court recognised commercial advertising as a part of freedom of speech under Article 19(1)(a). The Court held that advertisements are not merely profit-driven promotions but vehicles of information that allow consumers to make informed decisions. Restricting such communication would limit market transparency and public access to knowledge. By elevating commercial speech to constitutional protection, the judgment clarified that democratic expression includes economic expression, and that consumers have a right to receive truthful, market-relevant information.

A citizen cannot participate effectively in market decisions without access to relevant information. When economic decisions shape national life, commercial communication becomes an extension of expressive liberty.

Digital Speech and Modern Democratic Accountability

The internet has transformed the citizen from a passive observer into an active critic.

Online journalism, public commentary through live sessions, investigative channels on video platforms, and social media critiques now function as instruments of civic involvement.

A student in a small town can unmask administrative negligence as effectively as a metropolitan correspondent. A labour union can broadcast its grievances in real time. A researcher can publish findings beyond institutional gatekeeping.

What is Digital Speech?

Digital speech refers to all forms of expression communicated through online and electronic platforms, including social media posts, livestream commentary, podcasts, blogs, online journalism, satire channels, and independent political critique. Under Article 19(1)(a), these modern voices receive the same constitutional protection as traditional speech, ensuring that dissent, reporting, and civic participation remain robust in the digital era. The law recognizes that democracy today operates not only through printed headlines and public rallies, but also through hashtags, investigative threads, and real-time citizen reporting.

Digital expression is no longer peripheral; it is central to public participation. Courts have repeatedly acknowledged that constitutional protection extends to online dissent, policy critique, satirical content targeting governmental decisions, and investigative disclosures that reach millions at once.

The Constitution remains technologically impartial. It does not prefer quill to keyboard, ink to touchscreen, or editorial desk to handheld device.

What it protects is the essence of expression: the human need to articulate truth, opinion, and dissent without institutional intimidation.

The Essential Constitutional Understanding

Article 19(1)(a) does not merely shield communication. It promotes national growth by permitting dialogue. A democracy that only tolerates agreement is a democracy in decline.

Real freedom is demonstrated not by the liberty to praise but by the liberty to question.

Expression evolves because liberty evolves. A Constitution that respects speech must also respect its silence, satire, commerce, emotion, and creativity.

In all its forms, communication remains at the heart of democratic life. When expression flourishes, society breathes. When it is suppressed, constitutional promise withers.

Article 19(2): Reasonable Restrictions on Article 19(1)(a)

Article 19(1)(a) opens the gates of expression, but Article 19(2) ensures that the gates do not turn into floodwaters.

The framers did not wish to manufacture an unregulated marketplace of words where disruption masquerades as liberty.

Thus, Article 19(2) stands as the constitutional safety-valve, ensuring that speech remains powerful but not poisonous.

The provision states that freedom of speech can be curtailed only on enumerated grounds. These grounds are not expandable by convenience, creative interpretation, or executive fear. Each is narrowly carved, legally defined, and judicially monitored.

Sovereignty and Integrity of India

Speech that attempts to violently dismember India’s territorial unity, encourage armed insurrection, or call for forcible separatism falls into this category.

However, advocating federal restructuring, demanding state autonomy, or critiquing central policies does not offend sovereignty. Citizens may demand reform, but cannot advocate violent disintegration.

⚖️ CRITICAL PRECEDENT

Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar (1962)

The Supreme Court upheld sedition’s validity but limited it to speech inciting violence or rebellion. Mere political criticism was held not to threaten sovereignty. This judgment shielded dissent from being labelled anti-national.

The Court has kept this ground tightly sealed: patriotism cannot be confused with silence, nor can dissent be mistaken for disloyalty.

Security of the State

Security is not an emotional category but an objective constitutional threshold. A newspaper headline that embarrasses government agencies does not endanger the “security of the State.”

Security concerns arise when speech:

- incites armed rebellion,

- facilitates espionage,

- encourages attack on military bases,

- or deliberately leaks classified intelligence.

Merely questioning policy decisions or exposing administrative failure may discomfort power, but discomfort is not a constitutional restriction.

⚖️ CRITICAL PRECEDENT

Ram Manohar Lohia v. State of Bihar (1960)

The Court held that only actions posing a direct threat to national security justify restriction. Mere passionate speeches were not enough to invoke State security concerns. The doctrine curbed the misuse of preventive detention.

Friendly Relations With Foreign States

This head is rarely invoked, and rightly so. The Constitution does not prohibit critique of international policy or diplomatic decisions.

What it restricts is:

- malicious propaganda aimed at disrupting foreign relations,

- deliberate diplomatic provocation,

- or incitement that publicly ridicules, abuses, or threatens partner nations with hostility.

A critical op-ed on global trade policy remains lawful. A speech calling for war based on outrage and rumor crosses constitutional lines.

⚖️ CRITICAL PRECEDENT

Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978)

The Court insisted that restrictions impacting foreign relations must satisfy fairness and non-arbitrariness. Diplomatic embarrassment does not automatically justify silencing expression. The ruling strengthened procedural protections.

Public Order

The Supreme Court has drawn a careful distinction between public order and law and order. Every heated speech does not equal a riot.

- “Law and order” involves localized disturbances.

- “Public order” requires a broader threat to civil peace.

The classic test: Does the speech directly and imminently create chaos?

⚖️ CRITICAL PRECEDENT

Superintendent, Central Prison v. Ram Manohar Lohia (1960)

The Court differentiated between law and order, and public order. Speech must have a proximate and real likelihood of disorder to justify restriction. Irritation or unrest is not enough to curtail freedom.

If a speaker merely offends sensibilities, it remains protected. If the same speech instructs people to burn, harm, loot, or forcibly disrupt civic life, restrictions become lawful.

Offence is not disorder. Irritation is not riot.

Decency or Morality

Morality evolves, but censorship cannot evolve at the same emotional pace. Courts have avoided imposing Victorian modesty on modern expression.

Nudity in art, passionate literature, or socially progressive cinema may disturb conservative tastes, yet remain constitutionally valid.

Legal morality must be distinguished from cultural discomfort.

Decency cannot become a mask for suppressing feminist writing, queer identity representation, or critical depiction of patriarchal structures.

⚖️ CRITICAL PRECEDENT

Aveek Sarkar v. State of West Bengal (2014)

The Court rejected the archaic Hicklin test and applied the modern community standards principle. Artistic nudity was not inherently obscene. This judgment protected evolving cultural expression.

A society cannot grow if expression is forced to tiptoe around outdated sensibilities.

Contempt of Court

Judiciary protects speech; the judiciary also protects its authority. One may criticize judgments, question legal reasoning, or disagree with verdict consequences. But one cannot:

- launch defamatory slander against judges personally,

- obstruct court functioning,

- or lower institutional integrity through baseless accusations.

A lawyer may critique a judgment sharply with analytical depth. The problem arises when critique descends into insult, rumor, or malicious personal attack.

⚖️ CRITICAL PRECEDENT

E.M.S. Namboodiripad v. T.N. Nambiar (1970)

The Court clarified that fair criticism of judicial conduct is allowed, but personal attacks eroding institutional faith are not. This preserved judicial dignity without demolishing democratic critique.

The dignity of the institution shields justice, not judges’ pride.

Defamation

Article 19(2) protects reputation as a component of dignity. Free speech does not include freedom to assassinate character.

Fair criticism, editorial scrutiny, and truthful investigative journalism remain safe. What crosses the line is:

- deliberate fabrication of allegations,

- personal smear designed for humiliation,

- or malicious falsehood printed as “news.”

⚖️ CRITICAL PRECEDENT

Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India (2016)

The Court upheld criminal defamation, recognizing reputation as a constitutional facet of dignity. Free speech cannot become a shield for malicious harm. The judgment balanced voice with responsibility.

Law does not ask citizens to whisper, but it asks them to speak with honesty.

Incitement to Offence

This ground carries the sharpest judicial teeth. Speech that tells someone to hate is troubling; speech that instructs someone to attack is unconstitutional.

⚖️ CRITICAL PRECEDENT

Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015)

The Supreme Court struck down Section 66A of the IT Act for punishing vague online speech. Only direct incitement to violence or unlawful action may be penalized. This case constitutionalized digital free speech protections.

Incitement requires direct intent and immediate consequence:

- “We disagree with their ideology” is protected.

- “Chase them, harm them, burn their houses” is criminal.

The threshold is not emotional hurt but actionable violence.

The Constitutional Importance of the Word “Reasonable”

Article 19(2) uses the word “reasonable,” and the judiciary treats it as the constitutional guard dog. Not every restriction is reasonable simply because authority writes a notification. The State must prove:

- proportionality (no excessive control),

- necessity (restriction must be last resort),

- nexus (restriction must directly relate to harm),

- non-arbitrariness (not based on dislike or discomfort).

Convenience is not a constitutional ground.

Governments may change their seats, parties, manifestos, or narratives, but they cannot change foundational liberties.

Leadership may dislike criticism, but public office carries with it the burden of scrutiny. Administrative embarrassment is a political cost, not a constitutional justification.

State Cannot Restrict Speech on Convenience

If governance becomes fragile every time a citizen speaks boldly, democracy shrinks into ceremony. If every critique is labeled sedition, every satire criminalized, and every whistleblower silenced, the republic becomes ornamental rather than functional.

- A minister may dislike a cartoon; the cartoon is still legal.

- A leader may feel wounded by investigative reporting; the reporting remains protected.

- A policy may face public outrage; outrage is part of democratic negotiation.

The Constitution does not exist to make the State comfortable; it exists to make the citizen empowered.

When Article 19(2) is stretched to defend insecurity instead of security, power becomes censorship.

Article 19(1)(a) gives citizens a voice; Article 19(2) ensures that voice is used without igniting violence or destroying institutional dignity.

The relationship is not antagonistic but protective. Restrictions exist not to mute, but to moderate; not to suppress, but to secure.

A democracy cannot breathe if every sentence requires permission. Yet it cannot survive if speech turns into weaponized hostility.

The Constitution, therefore, crafts a careful bridge, strong enough to hold dissent, firm enough to prevent chaos.

Freedom remains the RULE.

Restriction remains the EXCEPTION.

Landmark Judicial Interpretations on Article 19(1)(a)

How the Supreme Court sculpted the spine of free speech in India?

Indian constitutional jurisprudence is not created in silence; it evolves through fearless judgments, constitutional battles, and courtroom debate.

Each decision below did not merely interpret Article 19(1)(a) but also strengthened and clarified what it means to speak freely in a democratic Republic.

Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950)

Press cannot be silenced unless public order truly demands it

This decision came when India was still learning how to breathe as an independent democracy. The Madras government imposed restrictions on a political journal, justifying it under the broad excuse of “public safety.”

The Supreme Court made an emphatic declaration: freedom of the press stands at the core of free expression.

The State cannot simply pull the plug on publications because they make the government uncomfortable or ideologically restless.

It held that:

- “Public order” concerns cannot be imagined; they must be real, imminent, and provable.

- Criticism or dissent cannot be filed under “danger to security” just because it is unflattering.

This case is often described as the first loud knock on the door of State censorship in free India.

The Court signaled that the Constitution will not tolerate bureaucratic nervousness masquerading as national interest.

Brij Bhushan v. State of Delhi (1950)

Prior restraint is a constitutional sin

If Romesh Thappar lifted the volume of the free press, Brij Bhushan clarified the rules of the sound system.

The Delhi administration attempted prior scrutiny of newspaper content before publication, essentially censoring thought before it was even printed.

The Supreme Court noted that such preventive censorship strikes at the spinal cord of Article 19(1)(a).

Key takeaways:

- Freedom of expression includes the freedom to publish without pre-approval.

- The State is not the editor-in-chief of the Republic.

- Democracies review speech after it is spoken, not before it takes birth.

This case is celebrated for drawing a constitutional Lakshman-Rekha: the government cannot demand a preview of criticism before allowing it to reach citizens.

Bennett Coleman & Co. v. Union of India (1973)

Press control via supply control is still censorship

In this case, the government thought it had found a clever shortcut: restrict newsprint supply rather than censor the content directly. Reduced paper meant reduced pages, fewer columns, fewer viewpoints.

The Supreme Court saw through the tactic with clinical precision.

“Limiting news production is limiting ideas.”

That sentence is not merely a judicial observation; it is philosophy wrapped in law.

The Court stated:

- Freedom of expression includes freedom of circulation, not just publication.

- Indirect restrictions are as unconstitutional as direct bans.

- Market regulation cannot be used as a political muzzle.

The judgment reinforced that press freedom is not gift-wrapped by the State; it is guaranteed by the Constitution.

S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989)

Intolerance of a few cannot hijack public discourse

A film faced severe backlash from groups claiming offense. The government, instead of safeguarding creative liberty, chose the easier path, restrict the film.

The Supreme Court delivered one of the most powerful lines in Indian free speech history:

“Freedom of expression cannot be suppressed on account of threat of demonstration or violence… The State cannot plead its inability to handle the hostile audience.”

In simple language, if a few people shout, you do not gag the artist; you strengthen the law and order machinery.

Core principles affirmed:

- Moral policing cannot replace constitutional policing.

- Public intolerance is not a ground for State-sponsored censorship.

- Creative freedom exists not only for agreeable content, but precisely for the provocative, critical, and uncomfortable.

When society says “Do not show this, it upsets us,” the Court gently replies:

Democracy was never meant to guarantee emotional comfort.

Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015)

Digital dissent is as sacred as printed dissent

Section 66A of the IT Act allowed arrests for vague offences such as “annoying” or “offensive” online posts, terms so broad that even political satire or strong opinion could land a citizen in jail.

The Supreme Court struck down Section 66A entirely, defending the modern citizen’s keyboard with the same dignity once reserved for the printing press.

Key clarifications:

- Only speech that incites imminent violence or illegal action can be restricted.

- Vague expressions like “irritation,” “offense,” or “annoyance” do not qualify as constitutional grounds.

- The Internet is not a lesser platform of liberty.

The judgment acknowledged that digital expression, memes, satire, online journalism, podcasts, and social media activism are protected by Article 19(1)(a).

India officially entered the era where a tweet, a blog, or a YouTube exposé stands shoulder to shoulder with a newspaper editorial in constitutional sanctity.

Courts as Guardians, Speech as Lifeblood

Across decades, from inked paper to digital pixels, the judiciary has reaffirmed one truth:

Freedom of speech is not an ornament of democracy; it is its bloodstream.

Each judgment above not only settled a dispute but expanded the democratic oxygen supply:

- Thappar established that the State cannot silence critique.

- Brij Bhushan forbade editorial pre-approval.

- Bennett Coleman crushed indirect strangulation.

- Rangarajan rejected mob veto.

- Shreya Singhal protected digital rebellion.

These rulings collectively ensure that:

- society may debate without fear,

- the press may investigate without permission,

- satire may sting without apology,

- and the citizen may speak without trembling.

The Constitution does not ask voices to be polite, agreeable, or flattering. It only requires them to be free.

Right to Criticize Government: The Constitutional Right to Speak Truth to Power

A democracy without criticism is not a democracy; it becomes plain administration occasionally perfumed with patriotic slogans to maintain appearances.

The framers of the Constitution, having suffered colonial censorship, sedition trials, and seizures of newspapers, did not envision Independent India as a passive listener to official declarations.

They intended a vibrant constitutional republic where citizens question, challenge, correct, and demand answers when power strays from public duty.

Criticism: Not Sedition, Not Disloyalty, Not an Attack on the Nation

A seasoned constitutional lens makes it clear that criticizing government policy is not the same as attacking India. Governments change, cabinets shuffle, alliances break, and ideologies rotate.

The nation, however, stands beyond electoral arithmetic. When a citizen points out budgetary error, administrative delay, policy flaws, or corruption in procurement, he is acting not against India but in defence of it.

If dissent reflects reality, suppressing dissent does not erase flaws. It merely hides them until they become unmanageable.

Judicial Clarity on Democratic Disagreement

The courts have spoken with consistent precision that criticism alone cannot qualify as sedition.

In Kedarnath Singh v. State of Bihar, the Supreme Court held that strong criticism, even if harsh or unpleasant to those in office, is not sedition unless accompanied by incitement to disorder or a concrete call to violence.

The constitutional test is deliberate provocation of public disorder, not discomfort caused to political leadership.

Thus, pointing out inflation, long-standing agricultural distress, regulatory arbitrariness, or delayed justice does not invite penal consequences. The threshold remains high because a free republic must not tremble at words.

Patriotism Is Not Measured by the Volume of Applause

Patriotism is not an oath of constant praise. A citizen devoted to the well-being of the Republic must reserve the right to ask questions.

True allegiance sometimes appears in the form of inconvenient inquiry and not in the performance of national cheerleading.

A population that never questions authority is not patriotic; it is merely obedient. Constitutional democracies deserve thoughtful citizens, not silent spectators.

Public Critique as a Democratic Responsibility

Editorial critique, investigative journalism, academic inquiry, legal petitions, peaceful rallies, and citizen commentary are not constitutional favours but democratic functions.

When a newspaper investigates misuse of public funds, it does not tarnish the State; it safeguards the treasury.

When a university audit exposes administrative mismanagement, it is not undermining the government but reinforcing accountability.

If citizens are permitted to vote but forbidden to question, then the ballot becomes ceremonial rather than sovereign.

A Gentle Look at Political Sensitivity

With a measured hint of courtroom humour, one must acknowledge that certain governments historically develop a curious sensitivity to criticism.

A cartoon, a theatre performance, a tweet, or a street satire sometimes produces more official anxiety than a failed policy.

The Constitution, however, has thicker skin. It does not lose sleep over expressive exaggerations, election memes, or a mild joke on bureaucratic paperwork delays.

A nation in possession of millennia of debate, negotiations, and philosophical contest does not fear satire. The appropriate remedy for criticism is an answer, not suppression.

Dissent Strengthens the Republic

The right to criticize government strengthens, not weakens, constitutional culture. Whether the dissent is loud, poetic, quiet, analytical, or humor-laced, it remains a safety valve.

Without criticism, power calcifies. Without public questioning, representation becomes reduced to ritual.

A nation confident in itself listens. A nation unsure of its own democratic foundations silences.

Criticism is the Lifeline of Liberty

Democracy is not a muttering choir of agreement. It is a marketplace of opinions where voices differ, conflict, argue, and educate one another. Article 19(1)(a) protects this diversity not as decoration but as a democratic necessity.

A government at ease with scrutiny is a stable State. A government that fears criticism stands on fragile constitutional ground.

Political parties alternate, manifestos evolve, budgets recast themselves every fiscal year, but the right to speak must remain unshaken.

Silencing dissent does not build unity. It only produces silence, and silence has never been a substitute for freedom.

Press Freedom and Investigative Journalism

A democracy remains healthy only when those in authority accept that they can be questioned, examined, and even criticised. The press exists to ensure that power cannot hide behind privilege.

Article 19(1)(a), therefore, does not merely allow newspapers or media platforms to publish stories. It uplifts the press as a constitutional partner in maintaining transparency.

A journalist is not a mere recorder of events. The journalist is society’s interpreter, public investigator, and messenger of accountability.

Reporting is not limited to recounting facts but includes uncovering what the public has a right to know.

When public funds are misused, when constitutional safeguards are violated or when the vulnerable are silenced, the press serves as the bridge between truth and citizens.

The Supreme Court has consistently recognised this vital position.

Freedom of the press is woven into the words of Article 19(1)(a) even though it is not individually itemised. The absence of explicit mention does not diminish its protection.

The Constitution is clear: expression includes publication, circulation, criticism and journalistic inquiry.

Press Responsibilities

Freedom must walk alongside responsibility. The liberty to publish should not transform into the liberty to injure without cause.

Truth, therefore, remains the foundation of journalism. Ethical practice demands verification of facts, consultation of reliable sources, and a willingness to correct an error rather than conceal it.

The moment news becomes knowingly false, it ceases to be journalism and enters the realm of manipulation. The press is expected to safeguard public knowledge by presenting accurate information rather than unexamined rumour.

Responsible press conduct strengthens freedom of expression rather than restricting it.

A healthy democracy requires both fearless reporting and reliable reporting. Without integrity, exposure becomes spectacle, and spectacle without truth benefits only propaganda.

Whistleblower Expression

Whistleblowers represent the conscience of the Republic. They reveal what others conceal, whether it involves financial embezzlement, illegal detention, ecological damage, procurement scandal, or administrative distortion. Their role is not rebellion. It is a constitutional service.

Suppressing whistleblower disclosures merely because they embarrass an office holder, irritate a department, or expose misuse of privilege would violate Article 19(1)(a).

A democratic State must welcome facts even when uncomfortable. A government secure in its ethics does not fear scrutiny.

The legal system gradually acknowledges that whistleblowers do not harm the State. They protect it from internal corrosion. They alert society to injustice before it becomes irreversible.

Freedom of Artistic and Literary Expression

Constitutional expression is not confined to editorials or public speeches. Art and literature are equally protected under Article 19(1)(a).

An artist communicates not through legal argument but through metaphor, imagination, and interpretation. That form of expression remains as vital as political debate.

Creative expression often unsettles the audience. A novel exposing patriarchy, a film questioning religious rigidity, or a painting interpreting political excess is not produced to decorate drawing rooms.

It is produced to provoke thought, reveal contradictions, and force society to look at its own reflection.

The law does not demand that art must be polite. Courts have consistently clarified that a creative work cannot be banned solely because it is disturbing. Discomfort is not illegal.

Modern Judicial Approach to Obscenity

Obscenity restrictions still exist under Article 19(2). However, courts no longer rely on antiquated purity standards imported from colonial morality.

The judicial focus today examines artistic purpose, social context, and intended message. A scene or image cannot be censored merely because certain sections prefer not to view it.

A society that refuses artistic realism risks cultural stagnation. Literary and visual expression often addresses themes that ordinary conversation avoids.

Domestic violence, caste oppression, addiction, sexual identity, and political distortion have found their most effective voice through poetry, theatre, and cinema.

Art is not required to Praise Society

Art is free to interpret society without beautifying it. It may choose to highlight cruelty rather than perfection.

It may paint darkness rather than light. It may write about inequality, hunger, displacement or grief without offering superficial cheer.

To expect artists to produce only admiration is to misunderstand their constitutional right. The purpose of literature and art is not to praise power or soothe conscience.

It is to document truth in its raw form. Beauty in art may be harsh.

Truth in art may be unsettling. Yet both deserve protection so long as the intention is expression and not criminal harm.

Satire and Political Expression

Satire holds a special place within expressive liberty. Comedy and caricature do not merely entertain.

They expose hypocrisy with clarity that formal dialogue often cannot achieve. When a cartoon exaggerates a politician’s promise or a comic monologue criticises public policy, it fulfils a democratic function. Humour often succeeds where speeches fail.

Political criticism in humorous form is not disrespect. It is participation. When leaders fear humour, it is not humour that shows weakness but the leadership that cannot withstand gentle questioning.

Digital Platforms, Social Media, and the New Constitutional Frontier

Digital space has become the new constitutional battleground. Unlike the traditional press era where a small editorial desk filtered opinion, today every citizen wields a broadcast tool in their pocket.

A tweet can mobilize a protest, an Instagram reel can expose injustice, a podcast can dissect policy failures, and a viral video from a bystander can unravel police excesses within hours.

The genius of Article 19(1)(a) is that it does not limit expression to mediums known in 1950.

It stretches naturally to WhatsApp activism, YouTube documentary journalism, digital street theatre, political satire channels, encrypted dissent, and even meme-based critique.

Digital Protest as Constitutional Action

- Hashtags of protest are not mere slogans; they are modern public squares.

- Online petitions have transformed from symbolic gestures to instruments capable of altering policy.

- Livestreamed dissent makes censorship harder and accountability sharper.

A democracy cannot demand silence when technology allows participation at scale.

New Threats: The Invisible Hand of Algorithms

Traditional censorship had signatures and office seals. Today, expression can be muted silently:

- Shadow bans on dissenting pages

- Algorithmic de-prioritization of political critique

- Automated content filtering trained on biased datasets

If a protest post is buried beneath dance reels due to algorithmic design, the silencing is no less real. Thus, digital liberty requires not only State restraint but also platform transparency.

The Rising Epidemic of Cyber-Bullying

While speech is protected, harassment is not a liberty. Threatening activists, stalking journalists, and doxxing whistle-blowers, these are not expressions but assaults on civil liberty. A State cannot merely protect speech; it must protect speakers.

Digital expression, therefore, forms the newest frontier where privacy rights, speech rights, cyber law, and platform governance converge.

Courts, legislatures, and constitutional scholars must interpret liberty not as nostalgia but as a living, ever-evolving guarantee.

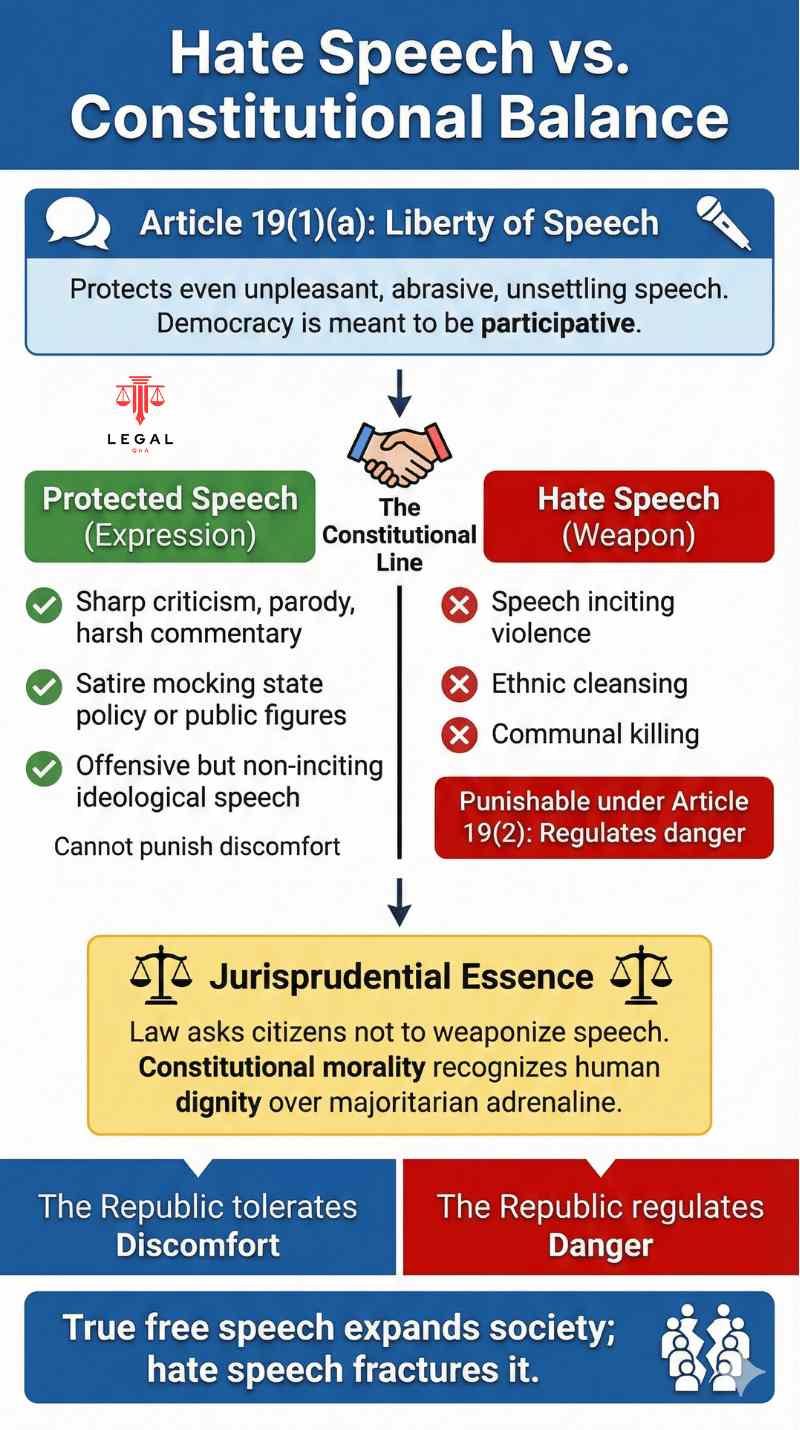

Article 19(1)(a): Hate Speech and Constitutional Balance

Article 19(1)(a) protects even unpleasant, abrasive, unsettling speech. Democracy is not meant to be comfortable; it is meant to be participative.

However, liberty crosses the line when speech becomes a weapon rather than expression.

The Constitutional Distinction

| Category | Constitutional Status |

| Sharp criticism, parody, harsh commentary | Protected |

| Satire mocking state policy or public figures | Protected |

| Offensive but non-inciting ideological speech | Protected |

| Speech inciting violence, ethnic cleansing, communal killing | Punishable under Article 19(2) |

A Constitution cannot punish discomfort; it can only regulate danger.

The Jurisprudential Essence

The law does not ask citizens to speak politely; it asks them not to weaponize speech.

Modern hate propaganda is often cloaked as nationalist masculinity or cultural purity. But constitutional morality recognizes human dignity over majoritarian adrenaline.

The Republic is not obliged to tolerate those who deliberately kindle riots, manufacture enmity, or broadcast exclusionary violence.

True free speech expands society; hate speech fractures it.

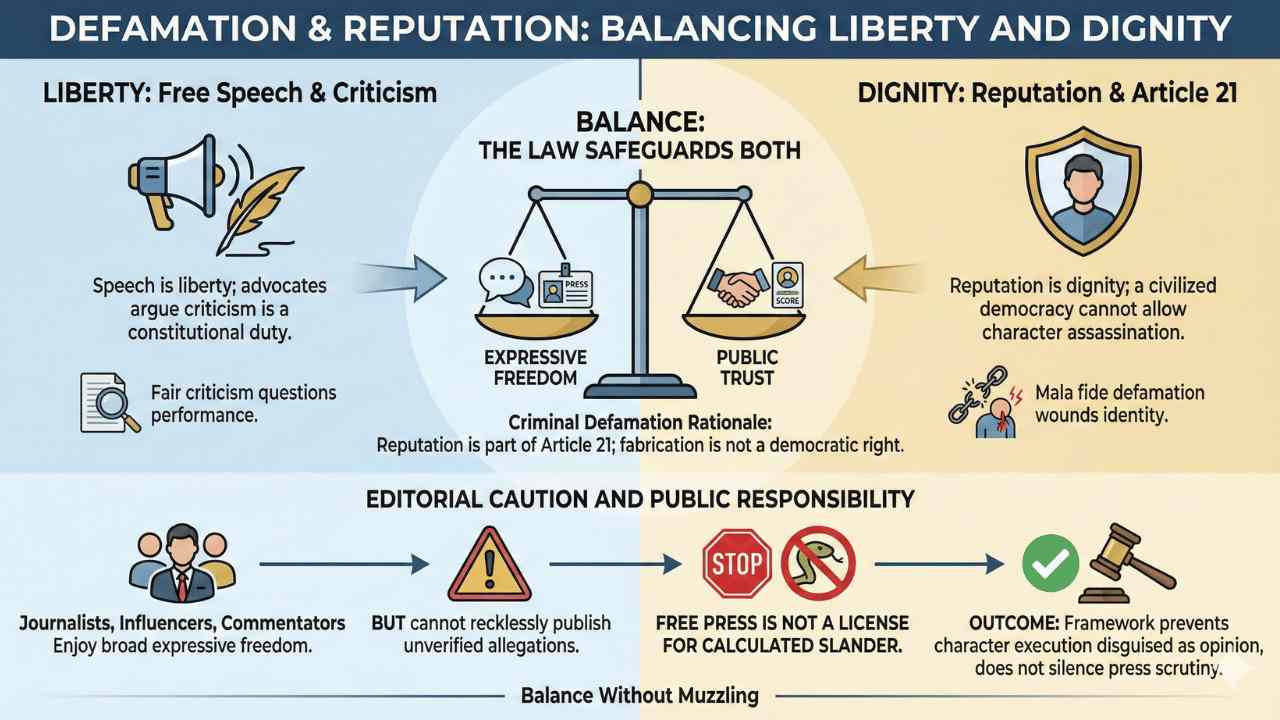

Article 19(1)(a) and Defamation & Reputation

Speech is liberty; reputation is dignity. The law must safeguard both. Advocates frequently argue that criticism is a constitutional duty, but character assassination is not a democratic right.

Criminal Defamation Rationale

The Supreme Court has clarified that reputation is part of Article 21. A civilized democracy cannot allow deliberate fabrication to destroy careers, social standing, or public trust through false allegations.

- Fair criticism questions performance.

- Mala fide defamation wounds identity.

Editorial Caution and Public Responsibility

Journalists, influencers, and digital commentators enjoy broad expressive freedom but cannot recklessly publish unverified allegations under the shield of activism.

Free press is not a license for calculated slander.

Balance Without Muzzling

The defamation framework does not silence press scrutiny; it simply prevents character execution disguised as opinion.

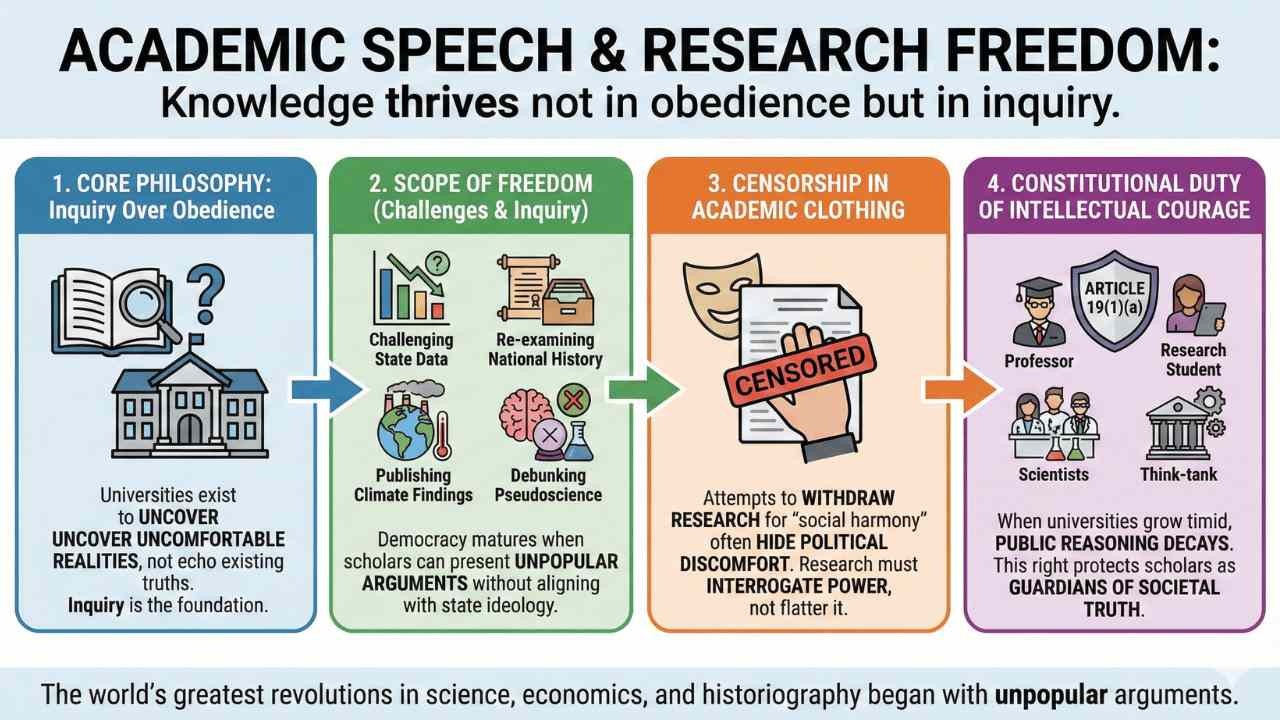

Academic Speech and Research Freedom

Knowledge thrives not in obedience but in inquiry. Universities exist not to echo existing truths but to uncover uncomfortable realities.

Scope of Academic Freedom

- Challenging state economic data

- Re-examining national history through archival evidence

- Publishing climate findings that implicate industrial houses

- Debunking pseudoscience endorsed by political narratives

A democracy does not mature if scholars feel compelled to align with state-approved ideology.

The world’s greatest revolutions in science, economics, historiography, and sociology began with unpopular arguments.

Censorship in Academic Clothing

Attempts to withdraw research on grounds of “social harmony” often hide political discomfort.

Research cannot be expected to flatter power; it must interrogate it.

The Constitutional Duty of Intellectual Courage

When universities grow timid, public reasoning decays.

Article 19(1)(a) therefore protects professors, research students, scientific communities, and independent think-tanks not as elite circles but as guardians of societal truth.

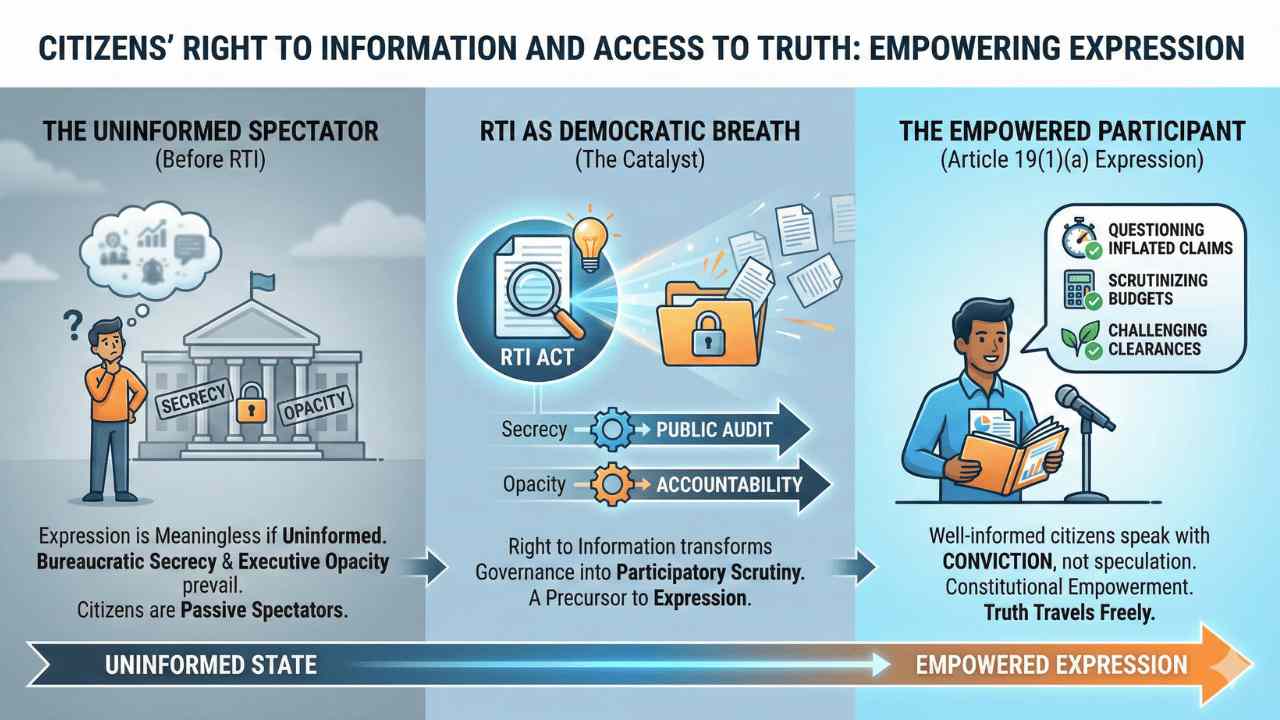

Citizens’ Right to Information and Access to Truth

Expression is meaningless if citizens are uninformed. The Supreme Court’s recognition of the right to receive information under Article 19(1)(a) turned spectators into participants.

RTI as Democratic Breath

The Right to Information transformed:

- Bureaucratic secrecy into public audit

- Executive opacity into documentable accountability

- Governance into participatory scrutiny

When people know, they speak with conviction, not speculation.

Information as a Precursor to Expression

A well-informed citizen questions:

- inflated development claims,

- unrealistic budget figures,

- environmental clearances granted in haste.

RTI is not administrative courtesy; it is constitutional empowerment.

Sedition and Democratic Morality

Sedition is a colonial ghost that still occasionally shakes its chains. It was crafted to punish those who demanded freedom from imperial control.

Ironically, it now sometimes targets those who demand accountable governance from a democratic state.

Judicial Retuning of Sedition

Courts have narrowed its scope:

- Speech must incite imminent violence.

- Mere anti-government sentiment is not sedition.

- Demanding change is not rebellion.

- Critiquing state policy is not treason.

A Confident Republic vs. A Fragile State

A democracy secure in its identity does not fear slogans, student protests, or satirical plays.

In fact, satire has historically been a constitutional disinfectant, exposing corruption far more effectively than polite memoranda.

When sedition is invoked against comedians, activists, journalists, and students, it reflects not national strength but governmental insecurity.

Other Landmark Judgments Defining the Scope of Free Expression in Indian Democracy

Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927)

- Facts: Charlotte Whitney was prosecuted under California’s Criminal Syndicalism Act for helping organize a political group whose ideology allegedly supported the violent overthrow of the government. The prosecution did not prove that Whitney herself advocated violence. Her mere association with the organization was used as the basis for conviction. She challenged the law as a violation of free speech protections.

- Judgment: The U.S. Supreme Court upheld her conviction, but the most influential aspect is Justice Brandeis’s concurring opinion. He explained that democracy must protect debate, disagreement, and advocacy unless the speech presents “clear, imminent, and substantial danger.” Brandeis stated that the remedy for dangerous ideas is more debate, not suppression. Fear of ideas is not a constitutional basis to punish speech. This principle later influenced global free speech jurisprudence. India’s modern interpretation of Article 19(1)(a), particularly its strict standard for restricting speech under Article 19(2), borrows conceptually from this case: speech cannot be punished unless it provokes actual unlawful action. Whitney remains a crucial philosophical foundation in comparing Indian and American approaches toward dissent and tolerance.

Union of India v. Naveen Jindal, 2004 (National Flag Case)

- Facts Industrialist Naveen Jindal began flying the national flag daily at his office and residence. Authorities claimed this violated the Flag Code and stated that hoisting was permitted only on certain days. Jindal asserted that flying the national flag was an expression of patriotism and thus protected by Article 19(1)(a). The Union government argued that national symbols could be regulated.

- Judgment The Supreme Court held that the right to fly the national flag is a form of symbolic speech protected by Article 19(1)(a). Patriotism expressed through a national symbol constitutes an expression of identity. However, the right is not absolute. The Court clarified that flag display must follow statutory dignity norms, including no damage or disrespect. The judgment expanded the meaning of expression beyond spoken or written language, recognizing non-verbal national identity displays as constitutionally meaningful. It also confirmed that emotional and symbolic participation in democratic life forms part of protected civic expression, establishing that independent India must not treat patriotic expression as a privilege, but as a liberty exercised with dignity.

Virendra v. State of Punjab, 1957 AIR 896

- Facts: Punjab and PEPSU governments enacted laws allowing temporary bans on newspapers and prior examination of articles during periods of political tension. Editors challenged the orders as excessive censorship that denied the press freedom to publish without state intimidation. The State argued that emergency conditions justified preventive measures to maintain order and avoid inflamed public sentiment.

- Judgment: The Supreme Court accepted that temporary preventive controls can be justified under Article 19(2) only if accompanied by strict procedural safeguards. It held that restrictions must remain narrowly tailored, time-bound, and subject to judicial review. The Court did not grant uncontrolled censorship powers, making it clear that extraordinary authority cannot become routine. The judgment shows the early judicial struggle to balance liberty with public stability. Although it upheld some emergency provisions, it warned the State that convenience or bureaucratic discomfort can never justify silencing newspapers. This case remains a reference point in assessing the validity of pre-censorship laws and prohibitory orders, reinforcing that restraint must never become repression.

Indian Express Newspapers v. Union of India, 1986 AIR 515

- Facts: Newspapers challenged import duties on newsprint, arguing that steep taxation would reduce circulation and limit editorial freedom. The Union government defended the levies as fiscal policy. The press asserted that heavy taxation operated as indirect censorship by restricting access to printing material essential to the dissemination of ideas.

- Judgment: The Supreme Court held that freedom of the press includes economic conditions necessary for its functioning. Though taxation is generally the government’s prerogative, if duties become instruments that effectively shrink circulation, weaken editorial independence, or restrict public access to information, they violate Article 19(1)(a). The Court allowed reasonable fiscal regulation but forbade using taxation as a disguised speech-control strategy. It emphasized that democracy depends on a financially unrestrained press. The case is frequently cited when indirect burdens on newspapers, such as advertising controls or import restrictions, are challenged as veiled censorship. It confirms that economic throttling can be as suppressive as editorial censorship.

Odyssey Communications Pvt. Ltd. v. Lokvidayan Sanghatana, 1988 AIR 1642

- Fact: A television serial featuring paranormal themes was accused by activists of promoting superstition and harming public rationality. They demanded prohibition of broadcasting, asserting it misled the audience. The channel argued that artistic creativity and viewer autonomy must prevail and that no legal violation occurred.

- Judgment: The Supreme Court refused to censor the programme, holding that viewers possess the choice to watch or avoid content and the State cannot suppress protected speech merely because certain groups object. Unless expression violates explicit constitutional restrictions, public order, morality, security, it must remain free. The Court criticized attempts by private groups to function as unofficial censor boards. It underscored that broadcasting is a legitimate expression avenue like print or theatre. This ruling reinforces that discomfort, disagreement or moral disapproval does not form legal ground for censorship. The State must not surrender expressive liberty to community pressure.

Association for Democratic Reforms (Disclosure Case), 2002

- Facts: Civil society organizations sought disclosure of criminal records, educational qualifications and financial assets of election candidates. The Election Commission initially resisted, claiming legislative power had priority over mandatory disclosures. Petitioners argued that voters cannot make informed electoral choices without full background access.

- Judgment: The Supreme Court ruled that voter’s right to know candidate information is part of Article 19(1)(a). It held that elections are not ceremonial procedures but democratic accountability mechanisms. Information empowers voters to scrutinize those seeking public office. The Court directed the Election Commission to mandate disclosures for all candidates. This case modernized Indian electoral democracy by converting passive voting into informed constitutional participation. It significantly transformed political transparency norms.

Hamdard Dawakhana v. Union of India, 1960 AIR 554

- Facts: The petitioners manufactured Unani medicinal products and advertised them extensively. The Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisements) Act imposed restrictions on advertisements related to cures for sexual ailments, infertility, enhancement claims, and miracle remedies. The manufacturers argued that the Act violated Article 19(1)(a) by restricting publicity and commercial promotion of their products. They maintained that advertising was a legitimate business expression and that consumers were entitled to receive information about available medicines.

- Judgment: The Supreme Court upheld the validity of the legislation, declaring that commercial advertisements lacking public interest are not protected as free speech under Article 19(1)(a). The Court reasoned that advertisements promising magical cures and commercial gains did not contribute to democratic discourse or social knowledge, and thus could be regulated to prevent exploitation. This case laid the early foundation that commercial speech is not equal to political or journalistic speech. Although later cases like Tata Press expanded protection to informational commercial speech, Hamdard Dawakhana remains relevant for distinguishing deceptive or exploitative content from genuine public communication.

K.A. Abbas v. Union of India, 1971 AIR 481

- Facts: Renowned filmmaker K.A. Abbas challenged the system of pre-censorship that required films to undergo compulsory examination by the Central Board of Film Censors (now CBFC). He argued that unlike books or newspapers, films were subjected to preventive censorship even before public release, thereby violating Article 19(1)(a). Abbas contended that such mandatory scrutiny was discriminatory and that artistic expression should enjoy freedom similar to the press.

- Judgment: The Supreme Court upheld pre-censorship of films, recognizing cinema as a medium with greater emotional and psychological impact than print. However, the Court insisted that censorship must follow fair, transparent, and non-arbitrary guidelines, including age-based classifications. It held that artistic freedom is vital but may be regulated to prevent glorification of violence, obscenity, or social disorder. Abbas remains the cornerstone for film regulatory jurisprudence, establishing that cinema is free expression but subject to structured and reviewable censorship standards, not discretionary suppression.

Indirect Tax Practitioners Association v. R.K. Jain, 1998 / NO.15 OF 1997

- Facts: R.K. Jain, a legal editor, published a detailed criticism of the functioning of the Customs, Excise and Gold (Control) Appellate Tribunal (CEGAT), highlighting procedural inefficiencies, suspected irregularities, and judicial delays. The tribunal initiated contempt proceedings alleging defamation and loss of institutional dignity. Jain asserted that his critique was truthful, fact-based, and within his constitutional right to comment on public institutions.

- Judgment: The Supreme Court held that fair criticism of judicial and quasi-judicial bodies is protected speech under Article 19(1)(a). It discharged contempt allegations, noting that a critique intended to improve the functioning of institutions is not defamatory contempt. The Court drew a crucial line: attacks that are malicious or purely scandalous may be punishable, but accurate institutional criticism strengthens the rule of law. This case shields journalists, academics, and professional analysts engaged in institutional evaluation, confirming that democracy requires open auditing of judicial and administrative bodies, not reverential silence.

PUCL v. Union of India, 2003 & 2013 (NOTA / Voter Expression Cases)

- Facts: The People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) filed petitions arguing that voters have the right not only to vote but also to reject candidates through a confidential mechanism. They asserted that the absence of such an option compromised electoral freedom, especially where all candidates failed to meet ethical or competence benchmarks. The Election Commission initially resisted, claiming legislative processes governed ballot rules.

- Judgment: The Supreme Court recognized NOTA (None of the Above) as an extension of Article 19(1)(a). The Court held that the right to reject is a form of political expression that enhances electoral honesty and deters corrupt candidacy. secrecy of voting was affirmed as integral to democratic choice under Article 21 and 19(1)(a). These rulings collectively transform voters from passive selectors to active democratic evaluators, shaping accountability at the ballot box.

AIR 1948 Nag 199 (Bhagwati Charan Shukla v. Provincial Government)

- Facts: This pre-Constitution case involved restrictions on circulation of publications deemed provocative under colonial emergency laws. The government argued that the material incited unrest. The publisher countered that criticism of government policies, even if sharp, could not lawfully be confused with sedition or disorder.

- Judgment: The Nagpur High Court recognized that while colonial law permitted censorship, criticism must be distinguished from incitement. It emphasized that public order requires deeper threshold than mere irritation or political discomfort. Later, this reasoning directly influenced early Supreme Court decisions like Romesh Thapar and Brij Bhushan, shaping the definition of “public order” under Article 19(2). The ruling is foundational historically: it seeded the doctrine that suppressing political voice does not create stability but erodes trust in governance.

Concluding Observation

Article 19(1)(a) is not a passive assurance but an enduring constitutional shield. Freedom dies not instantly but gradually, under silent compliance and self-censorship.

Every citizen, judge, legislator, journalist, and advocate carries a responsibility to defend it.

Speech may be uncomfortable, provocative, even disruptive, but democracy demands dialogue, not echo chambers. Once speech is shackled, the ballot loses meaning, accountability collapses, and society becomes obedient rather than free.

The Constitution does not ask citizens to whisper. It permits them to speak firmly, truthfully, and courageously.

Final Note

The legal beauty of Article 19(1)(a) lies not just in its drafting but in its interpretation: expanding, adapting, and protecting expression across generations.

From pre-censorship cases of the 1950s to digital rights in the 21st century, the Court has consistently affirmed that liberty, not fear, is the essence of the Republic.

Freedom of expression is the first guardian of all other freedoms.

When it stands, the Constitution breathes.

When it falls, every other right collapses silently.

Follow The Legal QnA For More Updates…

Article Sources

▾

The Legal QnA maintains the highest standards of accuracy and integrity in its legal content. Our writers and contributors rely on primary sources such as statutory laws, government notifications, regulatory circulars, and judicial precedents. We also incorporate insights from recognized legal commentaries, expert opinions, and academic publications where relevant. Every article is fact-checked and reviewed by qualified professionals to ensure it reflects current law and authoritative interpretation.

Refer to the official sources below for in-depth reading:

- Constitution of India: Articles 19(1)(a), 19(2) and 21.

- Parliament of India: Constituent Assembly Debates (Speeches on Fundamental Rights).

- Government of India: Right to Information Act, 2005.

- Supreme Court of India: Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras, AIR 1950 SC 124.

- Supreme Court of India: Brij Bhushan v. State of Delhi, AIR 1950 SC 129.

- Supreme Court of India: Sakal Papers (P) Ltd. v. Union of India, AIR 1962 SC 305.

- Supreme Court of India: Bennett Coleman & Co. v. Union of India, (1973) 2 SCC 788.

- Supreme Court of India: Indian Express Newspapers v. Union of India, (1985) 1 SCC 641.

- Supreme Court of India: S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram, (1989) 2 SCC 574.

- Supreme Court of India: Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, (2015) 5 SCC 1.

- Supreme Court of India: Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar, AIR 1962 SC 955.

- Supreme Court of India: Bijoe Emmanuel v. State of Kerala, (1986) 3 SCC 615.

- Supreme Court of India: Tata Press Ltd. v. Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd., (1995) 5 SCC 139.

- Supreme Court of India: K.A. Abbas v. Union of India, (1970) 2 SCC 780.

- Supreme Court of India: Odyssey Communications v. Lokvidayan Sanghatana, (1988) 3 SCC 410.

- Supreme Court of India: Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India, (2016) 7 SCC 221.

- Supreme Court of India: E.M.S. Namboodiripad v. T.N. Nambiar, (1970) 2 SCC 325.

- Supreme Court of India: Superintendent, Central Prison v. Ram Manohar Lohia, AIR 1960 SC 633.

- Supreme Court of India: Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, (1978) 1 SCC 248.

- Supreme Court of India: Union of India v. Association for Democratic Reforms, (2002) 5 SCC 294.

- Supreme Court of India: PUCL v. Union of India, (2013) 10 SCC 1.

- Supreme Court of India: Hamdard Dawakhana v. Union of India, 1960 AIR 554.

- Supreme Court of India: Indirect Tax Practitioners’ Assn. v. R.K. Jain, (2010) 8 SCC 281.

- Supreme Court of the U.S.: Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927).

- Legal Commentary: H.M. Seervai, Constitutional Law of India, 4th Ed.